Find Your Main Character's Flaws, and You Find Your Story

Flawed characters are just like you. But who are you?

We’ve been talking about the criteria in light of which a character’s wants are transformed.

But this implies that the character is in need of transformation. That the character has limitations. That the character has flaws.

One interesting writing guide encourages writers to kick-start story construction by thinking about their main character’s flaws:

“We’re going to start the writing process by taking a hard look at the person you think may be your main character. We’re going to figure out what that person is like before he or she hits page one, what his or her flaws are, [and] how those flaws can launch a story….

“Oh, your character doesn’t have a flaw? Well, mess him up. Get his hands dirty. Perfect characters are boring. Flawed characters are like us, and that’s what viewers respond to.”[1]

Flawed characters are like you.

Makes sense.

But who are you?

“Earlier novelists of the nineteenth century,” writes philosopher Charles Taylor, “like Jane Austen and Dickens, were grounded in a clear ethic, one which would have been recognizable to the majority of people in their time, and approved of by most (but, of course, not necessarily lived up to, which gives the novels of these authors their bite). Their ethics provided a steadying framework for the stories they told.”[2]

One thing the ghost at the machine of the 21st century is certainly not is one of “the majority of people” in Austen’s and Dickens’ times, one who “approved of” their “clear ethic.” You, today’s ghost writers, have no such “steadying framework” either for your own lives or for the stories you tell.

This does not mean that you don’t believe in anything, that you don’t have any commitments.

It means, rather, that whatever commitments you have are filtered by, appropriated through, your own “take” on those commitments.

If you’re an American, you are an American as you define “American.” If you’re a religious believer, you are a believer on your terms.

Because, as a ghost-self of the 21st century, you are more concerned with your authenticity, with your sense of your deepest and truest self, than with any abstract commitment to being an American or a religious believer.

This is why, as Charles Taylor explains, the concept of “identity” is so important to you. Your authentic self wants more than anything else to escape your doom as a specter that haunts the 21st century. Thus you seek registration of your authenticity in acts of appropriation. Such acts allow you to achieve a kind of embodiment, to escape the thinness of a life without commitments, though without giving up the sovereignty of your choice.

The upshot for your writing: you are flawed if you fail to achieve the half-life of authentic appropriation. And your character is flawed if he or she fails to do the same.

Yet the problem we began to identify in our last chapter remains. If your ideal of “your deepest and truest self” is the standard or criterion in light of which both your and your main character’s flaws are assessed as flaws, then there isn’t a standard or criterion of moral transformation apart from your own desires.

In the words of the playwright Tom Stoppard, we are left “marking our own homework.”

Why should that be troublesome, given that we live in a world—apart from the latest fixation with “manifestation”—which has largely forsaken “grand narratives” of meaning?

Well, because there is, arguably, a certain impoverishment, call it an “ontological impoverishment,” an impoverishment of being, that occurs when our own desires serve as the ultimate standard of our choices. As one spiritual writer puts it: “The exercise of human freedom is arbitrary and trivial unless it is a response to an invitation from something that transcends it.”[3]

That is, human freedom lacks weight, substance, if it itself provides its own direction to itself.

There is nothing nonarbitrary to call the self to escape its flaws.

No force of resistance to guide and correct its choices.

Accordingly, the self becomes weightless and insubstantial—like a ghost.

EXERCISE: THE MAIN CHARACTER FLAW BRAINSTORM

List ten possible flaws for your main character. Afterwards, review your list, asking yourself, first, by what criterion do I recognize these flaws as flaws? And second, does that criterion make my main character’s choices “arbitrary and trivial,” or does it provide sufficient resistance to allow my main character to achieve, not a mere half-life as a ghost, but real embodiment?

Write your brainstorm below.

[1] Pilar Alessandra, The Coffee Break Screenwriter: Writing Your Script 10 Minutes at a Time, 2nd edition (Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2016), 3.

[2] Charles Taylor, Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2024), 528.

[3] Jacques Philippe, Called to Life, translated by Neal Carter (New York: Scepter Publishers, 2008), 5.

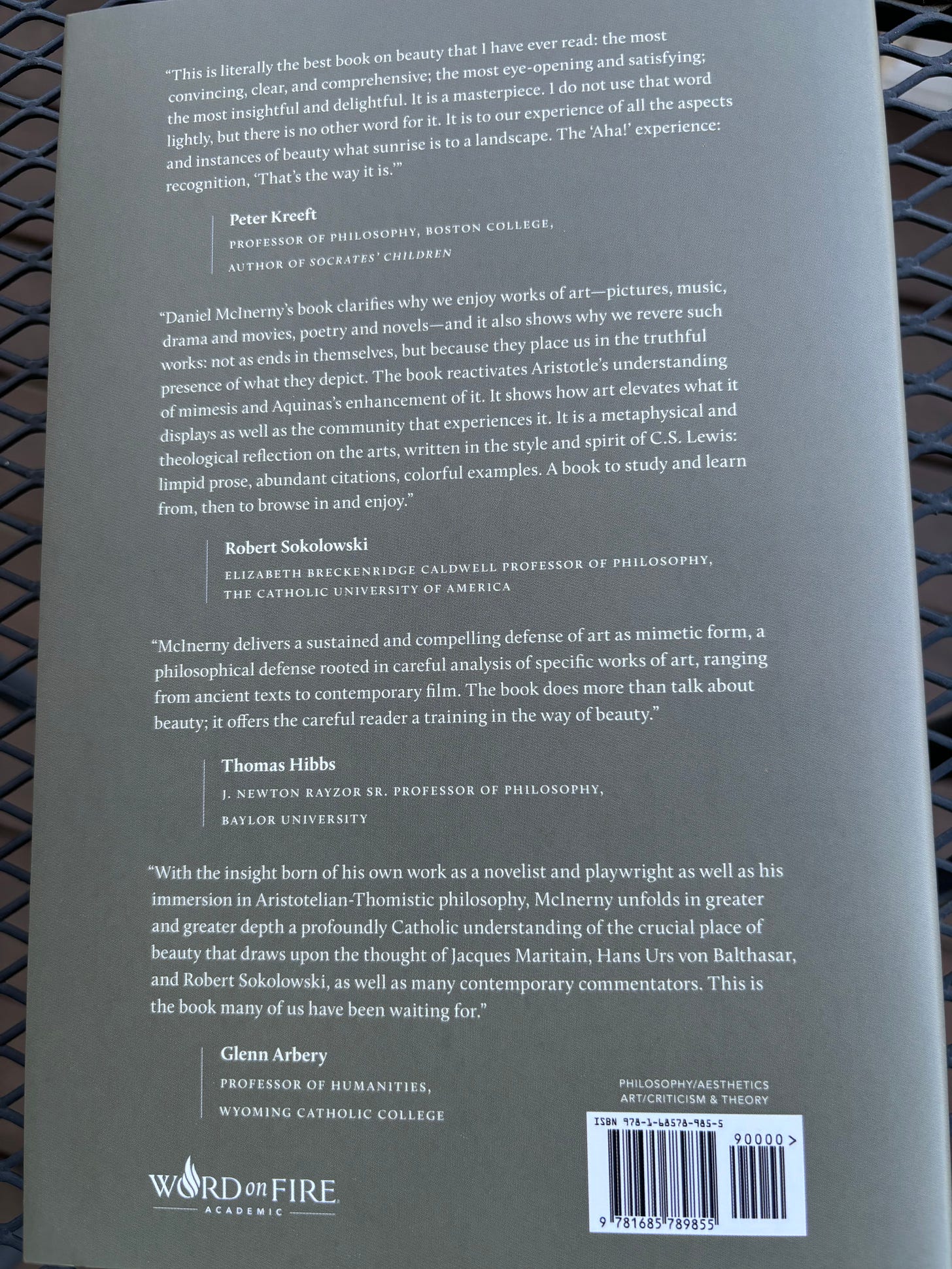

To my fellow educators, perhaps especially those who teach literature, art, drama, and music, you are INVITED to join me THIS THURSDAY, JULY 18, 2024, at 4:00 p.m. EST for a ZOOM Q&A on my new book from Word on Fire Academic: Beauty & Imitation: A Philosophical Reflection on the Arts, with a focus on how it might be of service to you in your course and curriculum planning for the coming academic year. No need to have finished or read the book (yet!) to participate in the Q&A. Just email your interest to me at danielmcinerny@gmail.com. To find out more about the book, go here…

If you’re looking for a great summer piece of fiction, I hope you will consider my novel, The Good Death of Kate Montclair, and, for the kids who are middle grade readers (approximately 9-14), my humorous Kingdom of Patria series.

Writing fiction in the first person, I have to live inside my narrator's flaws like a method actor, even though they aren't my own flaws, exactly. More like flaws I could imagine having if I leaned into certain tendencies, flaws-once-removed. It is a humbling exercise, because you find they are so easily to rationalize, slip into, even as you know they're flaws.

I suspect readers assume that the narrator is just like me (morally suspect & deeply flawed). An interesting exercise all around.