What Sort of Wanting Does a Character Need?

Character Transformation Seems to Imply More Than INTENTION + OBSTACLE

The writing guides all teach us that, first and foremost, the character must want something.

Aaron Sorkin, for example, is famous for saying that everything in the scene, and in the story, comes down to INTENTION + OBSTACLE: the protagonist’s want encountering stiff opposition.

For John Truby, “desire” is the very heart of what he calls the “dramatic code”:

“Desire in any of its facets is what makes the world go around. It is what propels all conscious, living things and gives them direction. A story tracks what a person wants, what he’ll do to get it, and what costs he’ll have to pay along the way.”

In the course of encountering stiff opposition, the character will, most of the time, change.

Says Truby:

“Any character who goes after a desire and is impeded is forced to struggle (otherwise the story is over). And that struggle makes him change. So, the ultimate goal of the dramatic code, and of the storyteller, is to present a change in a character or to illustrate why that change did not occur.”

There are stories in which the character undergoes no change whatsoever, like certain kinds of action-adventures. Sean Connery’s James Bond was not in search of a moral makeover. Nor is Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt.

And there is a form of satire structured by a cyclical movement in which a naïve, bumbling protagonist ends up, morally, right where he began. Cord Jefferson’s 2023 comedy-drama American Fiction is a recent satire that takes this form.

But these kinds of stories are the exceptions.

Most stories in every genre of storytelling—and all the greatest ones, I reckon—show a character undergoing a moral makeover in the encounter with the obstacles in the story.

At the end of Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet is not the same young woman she was at the beginning of the story, precisely because of her encounter with Mr. Darcy—the chief obstacle to her desire for happiness.

What I have been calling a moral makeover requires a transformation of want or desire. The dramatic conflict induces the protagonist either to exchange the original desire for some other, more appropriate one, or else deepen what was originally a superficial desire.

QUESTION: By what criteria do we say that a character’s desire has been “transformed”?

In other words, by what standard do we say that the character’s desire at the end of the story is “more appropriate” or “deeper”?

Here the writing guides are of little use.

Sure, they sometimes tell us that there is a distinction between what a character wants and what a character needs—a “need,” presumably, being a desire that is “more appropriate” or “deeper,” a desire the value of which the character must undergo much tribulation to discover.

But the writing guides don’t tell us which desires count as needs and which count as inappropriate or superficial wants.

They leave this distinction up to the individual storyteller.

And, in one sense, this is the right thing to do. For it is up to the storyteller, not the writing guide, to figure out his or her character’s moral transformation.

But, in another sense, the writing guide’s lack of direction tempts us to think that the distinction between character wants and needs is simply the distinction between an “ordinary” want and a “really, really important want.”

Thus we are led back to the question: what is it that makes a given want “really, really important?”

Is it possible that we need some criterion or standard outside the domain of “wants” or “desires”?

Is it possible to understand the drama of INTENTION + OBSTACLE as somehow manifesting, to both protagonist and audience, a criterion or standard which is not merely a matter of the storyteller’s “gut sense” of what the character should really want?

If so, what would be the basis of such a criterion?

a. God

b. The flourishing state of human nature

c. The lived moral consensus of our day and age (if there is one)

d. All of the above

e. None of the above

EXPLAIN YOUR ANSWER.

Brokeback Mountain, the film as well as the original short story by Annie Proulx, shows us characters engaging in sexual activity that, as viewed by Dante, would land those characters, if unrepentant, in one of the pits of Hell. One story universe shows us certain character needs as noble; another story universe shows us those same character needs as morally destructive.

How should we regard this situation?

a. We should count ourselves fortunate that we don’t live in Dante’s intolerant universe

b. We should simply acknowledge that we are living in a much different time than that of Dante, and admit that modern storytellers have different moral outlooks and allow them to write whatever they want to write

c. We should not try to compare “story universes” as if they were philosophical theories: they’re stories, for pete’s sake

d. We should wonder if, perhaps, one story universe more successfully manifests the true criterion or standard of human desire—and wonder, too, how the more successful story universe accomplishes this.

EXPLAIN YOUR ANSWER.

** If necessary, I ask forgiveness for borrowing the image above from K.M. Weiland’s website, Helping Writers Become Authors, and her post, “Creating Stunning Character Arcs, Part 3: The Thing Your Character Wants vs. The Thing Your Character Needs.”

McINERNY’S MUSINGS

The post above is the latest in my series: Ghost at the Machine: A Writer’s Manual for Apocalyptic Times. See the introduction to the series here.

I am so gratified by the reception that my new book, Beauty & Imitation: A Philosophical Reflection on the Arts, has received so far, especially from educators. As a former schoolteacher myself, I am eager to help secondary school educators, and even post-secondary educators, make good use of the arguments in the book in their course planning for the academic year that begins—Yipes!—next month. Toward that end, I will be hosting a Zoom Q&A especially for educators on THURSDAY, JULY 18, 2024 at 4:00 p.m. EST. You don’t have to have finished or even read the book (yet!) to participate. To get on the invite list, simply email your interest to me at danielmcinerny@gmail.com. As a former homeschooling dad, I am of course including home educators in this Q&A. Pass the word, and I’ll see you on the 18th!

By the way, the movie I mention above, American Fiction, is, at one level, a devastating and often extremely funny satire of the contemporary publishing industry. I found the movie overall unsuccessful, however, because the satire was only clumsily connected to the progressive family drama that ran alongside it.

Really enjoying the Euros, the Copa America far less so. Why are so many of the Latin American teams content to break their opponents down by crashing into them, knocking them over, and chipping away at their shins? Overtimes are boring in the Euros but I wouldn’t want to dispense with them, because maybe a coach will finally figure out that it’s better to try and win in overtime than risk losing in penalties. Euros prediction: Spain the winner. Copa prediction: all the players in the final will end up passed out bleeding on the pitch, with the score tied 0-0.

Christopher Lasch was a keen cultural critic of the 1980s and early 90s. I am right now reading his prescient 1984 volume, The Minimal Self, which seems 100x more true today than 40 years ago. Lasch offers a trenchant explanation of why our contemporary sense of self, as well as of our culture and politics, is saturated with a sense of victimhood and fragility.

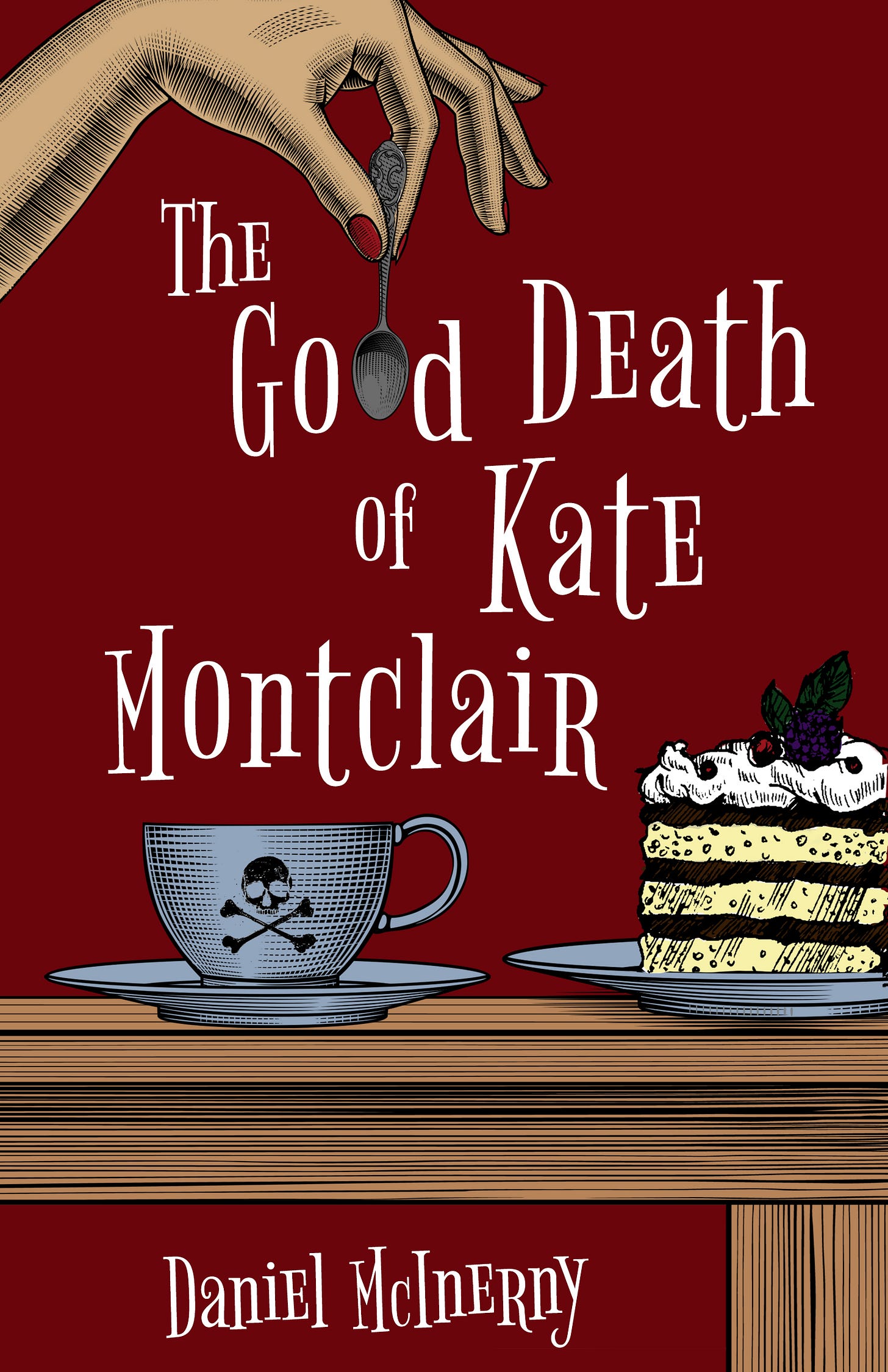

If you’re looking for a great summer piece of fiction, I hope you will consider my novel, The Good Death of Kate Montclair, and, for the kids who are middle grade readers (approximately 9-14), my humorous Kingdom of Patria series.

I’m looking forward to meeting with The Comic Muse subscriber Lisa Kearns’ book club on WEDNESDAY, JULY 17, 2024 at Rappahannock Cellars in Huntly, Virginia, to talk about The Good Death of Kate Montclair. If your book club would like to schedule a discussion with me about my novel, either live or via Zoom, please contact me at danielmcinerny@gmail.com.

a. You have been reading Lost in the Cosmos, haven't you?

b. I think of the structure of story somewhat differently. To me it is about placing a character in a situation where two of the things they love are incompatible with each other, forcing them to choose between them. That's not so different, but it allows that the impetus for the story may be loss as much as desire. The character may be preserving rather than seeking. And it does not require that either love be transformed, merely that one of them be chosen over the other. Such a choice may, of course, transform the life of the character, but not through the transformation of their desire so much as through a reconciliation between their loves.

This leaves, of course, the question of whether the character has chosen well, and whether each of their loves is appropriate and well-founded. But the moral weight of the story does not actually depend on answering those questions, for it is the moral burden of the choice itself that lies at the heart of the story, and one may feel the character has loved foolishly and chosen poorly and still be stabbed to the heart by the poignancy of the moment of choosing.

I adore John Truby's "Anatomy of Story," but I agree, we are lacking in direction of what exactly constitutes a frivolous want vs a super important need. And you're right, it comes down to what's important to each of us as storytellers.