On Making Art That Will Change the World

No art can hope meaningfully to address the malaise of modern existence without learning the secret of genuine authenticity.

In the 2017 film musical The Greatest Showman, about the origins of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus (starring Hugh Jackman as P.T. Barnum), there is a song called “This Is Me.” It is sung by a character named Lettie Lutz (played by Keala Settle), the “bearded lady” at Barnum’s circus. It is a stirring, defiant anthem. It begins with Lettie’s confession of the shame she has experienced on account of the public perception of her condition—

I am not a stranger to the dark

“Hide away,” they say

“Because we don’t want your broken parts.”

I’ve learned to be ashamed of all my scars

“Run away,” they say,

“No one’ll love you as you are.”

–but quickly turns into Lettie’s declaration of independence from this shame. Surrounded by the other so-called “freaks” from Barnum’s circus, Lettie sings: “No one’ll love you as you are, but—

I won’t let them break me down to dust

I know that there’s a place for us

For we are glorious

Then, in the chorus, these themes of courage and inherent self-worth reach their crescendo:

I am brave, I am bruised, I am who I’m meant to be

This is me

Look out cause here I come

And I’m marchin’ on to the beat I drum

I’m not scared to be seen, I make no apologies

This is me

Who among us cannot identify with Lettie Lutz’s sentiments in this song? It is a common human desire to be accepted, not only by others but by oneself, for who one is, however one is.

But it is interesting, and not insignificant for an understanding of our present cultural moment, that Lettie’s longing for acceptance and a sense of self-worth takes the form of a song, a work of art. This is because, for many in our culture, art is the primary way in which we move beyond so much that is oppressive in modern life and realize who we are truly meant to be.

Authenticity: Listening To Your Own Inner Voice

What Lettie sings about in “This Is Me” is our craving for authenticity, the life of the person we are truly meant to be, a person who is in some sense inside us, waiting to be discovered underneath the negative emotions we feel in regard to others’ perceptions and expectations.

The philosopher Charles Taylor summarizes the ideal of authenticity with these words:

“There is a certain way of being human that is my way. I am called upon to live my life in this way, and not in imitation of anyone else’s. But this gives a new importance to being true to myself. If I am not, I miss the point of my life, I miss what being human is for me.

Here in the United States, as well as in the mainstream cultures of other Western societies, authenticity is not simply one good among others. It is the summum bonum, the highest good, the state of perfect fulfillment. Any doubt about this fact can be dispelled by a tour of today’s popular culture, a tour that would showcase, along with “This Is Me,” Lady Gaga’s 2011 hit “Born This Way”—

I’m beautiful in my way

‘Cause God makes no mistakes

I’m on the right track, baby

I was born this way

Don’t hide yourself in regret

Just love yourself, and you’re set

I’m on the right track, baby

I was born this way (born this way)

–as well as all the films produced in the last 30 years by Disney and Pixar, the exhortations to “become your best self” by the legions of self-improvement gurus, and (arguably the purest specimen) Steve Jobs’ 2005 commencement address at Stanford University:

Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.

“Your own inner voice,” the voice that refuses to live with the results of other people’s thinking, the voice that has the courage to express itself—that is the voice of authenticity, and using it is the secret to living the life you were meant to live.

Start listening for motivational rhetoric on behalf of authenticity and you will hear it also in today’s political speech, in the brand development of business enterprises, and even in the messages of religious leaders, perhaps especially Christian ones.

The Buffered Self and the Struggle for Authenticity

We can only fully understand the power of authenticity if we understand what it is reacting against: what the philosopher Charles Taylor calls the modern condition of the “buffered” self.

The buffered self is the modern individual defined by nothing else but the activities of that individual’s own thinking and willing. Self-determination is the keynote of the buffered self, a self-determination made possible by disengaging from everything outside the self’s own powers. One’s ultimate purpose is found in one’s deepest psychic impulses, and the meanings of things defined by one’s responses to them.

Why call this modern individual a “buffered” self? Because the self is understood as existing securely within a kind of boundary or buffer such that (in Taylor’s words) “the things beyond don’t need to ‘get to me,’” and the self can see itself as “invulnerable, as master of the meanings of things for it.”

The buffered self might appear to embody the ideal of authenticity. The effort to be who one is truly meant to be, to listen to one’s own inner voice, seems to involve disengaging from any source of purpose or meaning outside the self.

But although there are clear connections between the buffered self and authenticity, the two ideals remain distinct. Authenticity, in fact, should be seen as a way of addressing the malaise of the buffered self.

What malaise? The malaise that comes from living in a disenchanted world, a world drained of purposes and meanings, a flattened and uninspiring world. What Taylor calls the social and cosmic horizons of action, which defined the narrative of the pre-modern self, are taken down by the modern project like a theatre set, leaving the buffered self alone on stage tasked with choosing its own adventure.

For many, at any rate, this is too large a creative burden to bear. Consequently, there is a loss of a sense of grand design and heroism, of hope and passion.

Afflicted by this malaise, many turn to the pleasures that are nearest and provide the fastest relief. And thus arises a culture of what Nietzsche calls the “last men,” whom we can recognize today, not just in those ensnared by our epidemic of pornography and opioid addiction, but in those whose only drama is that afforded by social media and the entertainments on their streaming platforms.

Yet for all its emphasis on being true to one’s deepest self, authenticity is not crudely egoistic or solipsistic. It wants to reconnect with what was lost in modernity’s dismantling of social and cosmic horizons. There are “horizons of significance,” as Taylor calls them, “backgrounds of intelligibility”—family, friendships, social and political institutions, religion or at least spirituality—that authenticity takes to be an eliminable part of any satisfactory life.

The image of Lettie Lutz flanked by the other so-called “freaks” from the circus as she proclaims her authenticity is emblematic of authenticity’s desire to find meaning outside the self, especially in solidarity with others. Lettie is no buffered Cartesian ego when she sings: “I know that there’s a place for us/For we are glorious.”

At its best, authenticity seeks to break out of the buffered self. This is evident in renewed spiritual searches, even by atheists, and in the variety of ways people seek to reconnect with the natural world through concern for our environmental future, in local initiatives such as farm-to-table restaurants, in odd yet oddly endearing movements like Cottagecore, and, since the Covid pandemic, in the exodus from urban centers to the countryside.

The principal means, however, of seeking authenticity and overcoming the modern malaise is the one with which we started: the arts. Since the Romantic period, art has been synonymous with the inner voice of authenticity. Art is the way in which authenticity is chiefly expressed. This means both that art has come to be identified with expression and that authentic expression is a kind of art, one which, like any art, requires a platform, if only Instagram or Tik Tok. The authentic individual can thus also be called the expressive individual, one whose heroes, like Lettie Lutz, express their inner voices in song and other works of art and by so doing transcend the oppressive immanency of being a buffered self.

Why Modern Authenticity Can’t Break Out of the Buffer

For modern individuals seeking authenticity, faith in God is one possible horizon of significance. He is on the menu of sources of meaning that emanate from beyond our psychic life. In “Born This Way,” Lady Gaga herself seems to acknowledge that God ultimately underwrites her authenticity:

My mama told me when I was young

“We are all born superstars”

She rolled my hair and put my lipstick on

In the glass of her boudoir

“There’s nothing wrong with loving who you are”

She said, “Cause He made you perfect, babe,

So hold your head up, girl, and you’ll go far.

Listen to me when I say…”

Yet the opening lines of the song indicate that such an understanding is only one option:

It doesn’t matter if you love him, or capital H-I-M (M,M,M,M)

Just put your paws up

‘Cause you were born this way, baby…

To understand the assumptions behind Lady Gaga’s song, it is necessary to imagine in our cultural life what Taylor calls a “neutral zone” between belief and unbelief. The expressive individual seeking authenticity wanders at least theoretically in this neutral zone until he or she chooses to adopt, or not to adopt, a belief in God.

But is this all that can be said for authenticity? One simply chooses whether one is going to believe in God, or have a family, or contribute one’s time to building up a school or a charitable work, and then one is living an authentic life?

On what basis do we choose our horizons of significance?

A song like “This Is Me” clearly is trying to thread the needle between narcissism and nihilism. It is very much striving to live up to the ideal of authenticity as defined in part by horizons of significance beyond the self.

But the imagination powering it still leaves too many options open, too many conflicting ways of declaring one’s bravery and sense of self-worth. We all want to find a community who will accept us for who we are. But that cannot mean that every declaration of self-worth is truly authentic.

For if choice alone is what makes meaning in our lives, then no choice is more significant than any other. If you declare that your authentic life consists in eating at every McDonald’s restaurant in the United States, there is nothing that anyone can say about it.

(And here is the philosophical weakness in J.K. Rowling’s attempts to draw a distinction between old-school progressive feminism and new-school progressive gender ideology. If everything comes down to choice, how can she draw this distinction? If everything does not come down to choice, then she must be depending upon some understanding of “woman” woven into the fabric of human nature—an understanding that may well undermine the feminism she ardently wants to defend.)

Significant choice is predicated upon there being sources of real value and meaning outside the self.

“This Is Me” is a hugely popular song in large part because everyone who hears it can read his or her understanding of authenticity into it. But this kind of art does not solve our problem in finding the truly authentic life. Its ambiguity only keeps the problem at bay. What our culture needs is art that gives us definitive and clear reasons for declaring one form of authenticity over another, reasons that are publicly available to everyone.

That kind of art, I contend, is what is offered by the Catholic imagination.

The Catholic Imagination as a Way Toward Genuine Authenticity

The Catholic imagination has three things in common with modern authenticity.

First, both recognize the flattened nature of so much of modern existence. Catholic novelist and philosopher Walker Percy diagnoses the modern malaise well when he speaks of our being “lost in the cosmos.” What he means is that, insofar as we have become buffered selves, disengaged from traditional social and cosmic horizons of significance, we have left ourselves with nowhere to be. We are not “placed” in the world in the way that a medieval Christian peasant regarded himself as “placed” in the world as a child of God, the subject of a king and local lord, and the father of a family. Gone, too, is our self-understanding as rational animals made in the image and likeness of God and given by God dominion over creation. Now the buffered self is no more than an organism-in-an-environment that interacts with other such organisms in sequences of purely material interaction. It is small wonder that modern people experience so much fear, anxiety, alienation, and lack of authenticity from having to exist in this condition. (I am drawing upon themes from Percy’s marvelous and very serious philosophical parody of self-help literature, Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1983). See especially the middle section entitled “A Semiotic Primer of the Self,” 85-126.)

Second, the Catholic imagination and modern authenticity share the aspiration to find an authentic “place” in the cosmos. This desire is wounded yet an essential human longing. Lettie Lutz represents the so-called “freaks” of P.T. Barnum’s circus who seek to find their place by expressing their inherent sense of self-worth.

But Flannery O’Connor, too, one of the 20th century’s most stalwart proponents of the Catholic imagination, is not insensitive to the importance of the “freak” in our culture—which in a sense is all of us. For O’Connor, the “freak” or “grotesque” that appears in so much 20th-century Southern fiction, and quintessentially in O’Connor’s own, is a figure for “our essential displacement.” The “freak” alone seems to have a sense that something is not right in himself and in the world around him. The “freak” alone seems to have a prophetic insight that there is mystery beyond the hankerings of self-determining freedom and longs, with a wounded desire, to realize a truer self within the depths of that mystery. Though the Catholic imagination presupposes a wounded yet legitimate desire for authenticity, I distinguish it from modern authenticity simply because it is not a development out of the modern conception of the self. (See O’Connor’s essay, “Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction.”)

Third, the Catholic imagination and modern authenticity both see art as one of the chief paths, if not the chief path, out of the malaise of the buffered self.

Yet the Catholic imagination differs from modern authenticity in one crucial respect: it has an understanding of reality that calls the artist and the artist’s audience to realities that are irreducible to, and so transcend, the individual and its powers of self-determination. The word that the ancient Greeks used for beauty, kalon, literally means a “calling.” Beauty in the Catholic tradition testifies to realities that transcend our material existence and to the intellectual and moral transformation those realities demand of us.

Only by recognizing those realities can the artist hope to achieve a meaningful authenticity, be healed of the malaise of the buffered self, and make an art that will change the world.

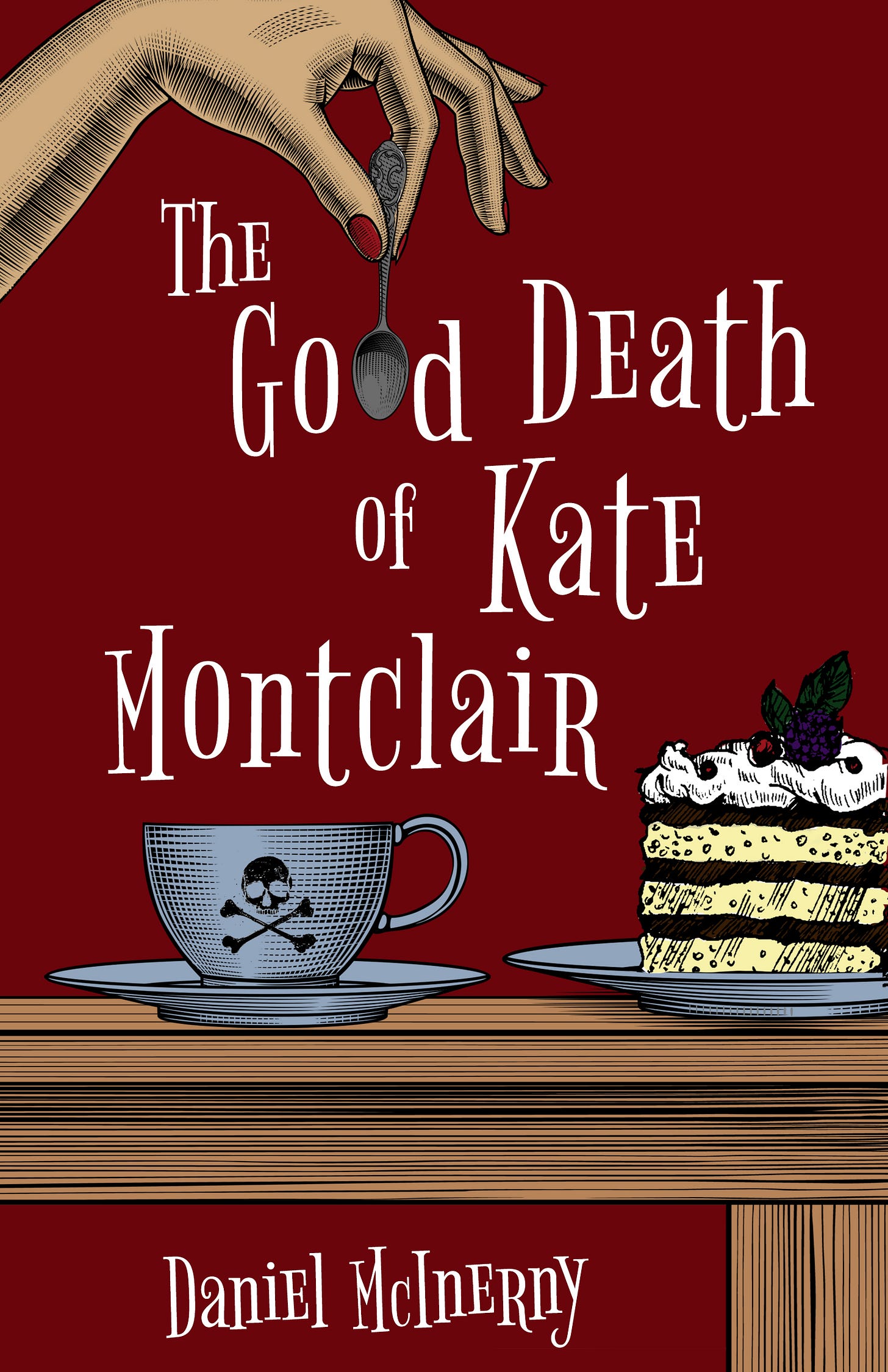

“At times, I found myself feeling as though I were reading Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited or Flannery O'Connor's Wise Blood, two works that differ drastically in tone and yet somehow find an easy harmony in The Good Death of Kate Montclair. I can't recommend the book enough.”

—from Katie S’s Five-Star Amazon review of THE GOOD DEATH OF KATE MONTCLAIR

The Good Death of Kate Montclair, is available here on Amazon and from Chrism Press.