Three-Act Structure Revisited

Including the time Sir Kenneth Branagh and I were not really that close to doing a project together

Pascal said, “The heart has its reasons that reason knows not of.”

But what are these “reasons” of the heart? How do we discover them?

And how are they different from scientific or philosophical reasons?

These are the questions I explore in my new short audio course, “A Brief Introduction to Poetic Experience.”

Not for poets only, but for anyone seeking to live more deeply in “being mode” rather than “doing mode.”

3 Segments. 1 Hour. A Whole New Way of Attending to Reality.

Perfect to take along on a walk, or on your commute, or while you’re doing the dishes.

Check out the details here…

Earlier this month I was in Houston to visit with students in the summer session of the MFA program at the University of St. Thomas. In the morning of my one full day there,

and I did a presentation on what it means to write in a genre. (Below I share my notes for my part of our presentation.)That evening, Rhonda and I were back on stage in the Cullen Hall Auditorium for readings from our work. I read some of the opening scenes from my novel, The Good Death of Kate Montclair, and what a delight it was. Never have I read my work to such an appreciative audience. They laughed at every possible comic element in the passages I read, and it was so encouraging to feel the auditorium erupt in laughter time and time again. This reaction confirmed for me that my story of a middle-aged woman struggling with a terminal cancer diagnosis is also, in its way, a very funny story.

I was also deeply touched by conversations afterwards with two of the MFA students. One was with an older man who, only three months ago, lost his wife to the very same inoperable cancer with which my protagonist, Kate Montclair, is afflicted (Glioblastoma Multiforme, Stage IV). Earlier in the day this man had told me, after hearing the premise of my novel, that he wasn’t quite ready to read it. But after my reading, he told me that he now wanted to read it right away.

The second conversation was with a woman who was a two-time cancer survivor. She wanted me to know that she had laughed harder during my reading than anyone else in the room.

It was a great night.

(If you’d like the student’s-eye view of the summer intensive related to the MFA program at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, see this recap by poet

.)(And if you’d like, you can check out the first chapter of my novel here, and you can purchase it here.)

Being on the campus of the University of St. Thomas put me in a nostalgic mood, as I taught in the philosophy department there, as well as in its Center for Thomistic Studies (its graduate program in philosophy), from 1994-2002. It was my first job out of graduate school. Houston was where my wife Amy and I began our married life (we’ll celebrate 31 blissful years of marriage next month). All our children were born in Houston, and baptized not far from the UST campus at the Dominican parish, Holy Rosary, where I was able to attend Mass after Rhonda’s and my morning session.

I had not stepped foot onto UST’s campus since the summer of 2002. I found that the building which housed my first three offices had been demolished, replaced by a large piece of landscape design with “UST” laid out in rocks. But I was able to look into some of the classrooms in Strake Hall where I had taught for eight years.

Dinner before the evening readings was with the MFA students in the Black Labrador pub. When I taught at UST it was a privately owned Irish pub, but now it’s owned by the university. Next door there is a branch of the public library. I remembered how, beginning in 2000, I used to go there during the lunch hour. Not to check out books. I went there to recommit myself to writing.

Since we had been in Houston, I had been writing short stories with a certain amount of seriousness. And earlier, before I was married, I had completed a couple of terrifically bad “novels.” But by 2000 I wanted to bear down on the craft more intensely, more professionally. If my memory is accurate, it was a desire to write screenplays that was driving me. And I am very grateful that, in that branch of the Houston Public Library, I came upon Linda Seger’s screenwriting guide, Making a Good Script Great.

I had never seen three-act structure explained before. I had no idea that movies—indeed, most stories—could be broken down in such a way. Seger’s book provided my first substantial lesson in the craft of storytelling.

What was I doing before I read Seger’s book, in terms of writing fiction? I made study of fiction, especially short stories. But I was mainly feeling my way through the process, trying to capture something of what I was experiencing in the stories I admired. But I really had no good idea of what I was doing—no sense of craft, of structure. Making a Good Script Great set me on my way. And how wonderful, a quarter of a century later, one of the fruits of that study, my novel, was showcased a stone’s throw away from where I discovered Seger’s book.

I’m quite sure that, without Seger’s book, I would not have, in early 2003, completed my first screenplay. I made one or two false starts, but it was after we had left Houston that I finally saw a screenplay to the end. The script is called I Am Not Prince Hamlet. It’s set in the theatre world of London’s West End. A frustrated actor understudying the lead in a production of Hamlet is visited by the ghost of his dead mentor, who claims he was murdered by the actor playing the lead in the production. The mentor now wants my hero to mete out his revenge by killing the lead actor in the production. You get it. The story of Hamlet is being recapitulated in my protagonist’s life, and like, Hamlet, my protagonist has to decide whether the ghost is telling the truth, or whether he is a demon sent to damn him. Big fun.

I Am Not Prince Hamlet secured me an agent with The Artist’s Agency in Los Angeles, which as far as I can tell is no longer in business. My agent was the late Dick Shepherd, who described himself to me as “the oldest agent in Hollywood” (he was then, I think, in his 70s). Dick enjoyed a previous show business existence as a producer, and you can go to IMDB.com and find him credited as a producer on Breakfast at Tiffany’s, among other films. I will never forget the day Dick told me on the phone that mine was the best first screenplay he had ever read. Perhaps he said this to all the screenwriters, but he put me over the moon all the same.

And Dick did a fantastic job getting some high-level readings of my script. Scott Rudin’s company read it, as did Mel Gibson’s. Kenneth Branagh’s lawyer read it, as did Lindsay Doran (herself, I think?). Doran was the producer of the Ang Lee adaptation of Sense & Sensibility with Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet.

Alas, of course, there was no sale from these or any of the other readers. I got some encouraging feedback, though, along with some more blunt rejection. I remember Dick describing to me how he wanted to approach Branagh’s lawyer with the project. Imagining himself talking to the lawyer, Dick said something like, “He [Branagh] doesn’t need to come with his tights on; we just want him to have a look at it.” Or something like that. Big fun.

But all that business (or lack of business) aside, it is most emphatically the case that, years later, when I was writing The Good Death of Kate Montclair, Seger’s Making a Good Script Great, along with many other sources, was still functioning as part of my far better-informed sense of the craft of storytelling. And for that I remain grateful.

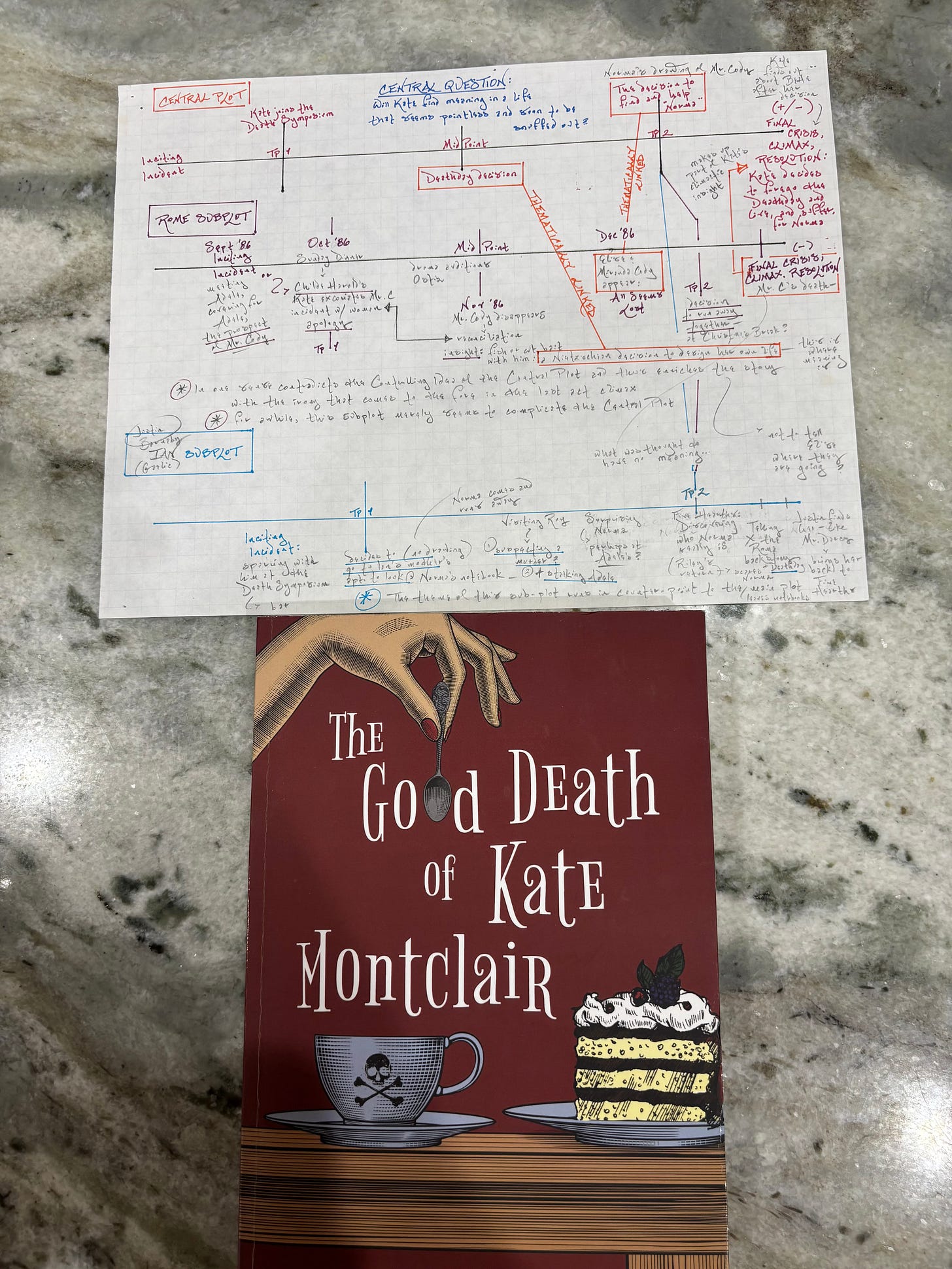

An early plot chart for The Good Death of Kate Montclair, showing the influence of Linda Seger’s teaching on three-act structure.

Here are the thoughts I shared with the UST MFA students on genre. Would love to hear your comments on them if they provoke some thoughts…

4 Thoughts About Genre in 15 Minutes

1. “Genre” (as we’re using it today) is Not the Same as “Marketing Category”

· Marketing genres may track genres in the literary sense, but only imperfectly. What publishers and booksellers take as “genre” is due in large part to marketing considerations.

· Marketing categories track the zeitgeist, and so are fluid. So that now we have not only “Women’s Fiction,” but “Book Club Fiction,” “Uptown Women’s Fiction,” etc.

· To write with an explicitly Catholic imagination is to put oneself at odds with the zeitgeist and mainstream publishing, at least when it comes to literary fiction.

2. A Genre is Simply One of the Narrative Forms that Picture the Human Quest for Ultimate Fulfillment

· That’s what a story is: an account of a protagonist’s search for happiness (see my book: Beauty & Imitation: A Philosophical Reflection on the Arts).

· So, there are three “master” genres. An action in pursuit of happiness can end well (comedy), not so well (tragedy), or with an ironic mixture of success and failure (what I will call, following David Mamet, “drama”).

· David Mamet, “Theatrical Forms,” from his book, Theatre:

“The theatre exists to present a contest between good and evil. In both comedy and tragedy, good wins. In drama, it’s a tie….

“Comedy and tragedy are concerned with morality, that is, our relations under God; drama with man in society….

“The theatrical interchange, then, is a communion between the audience and God, moderated through a play or liturgy constructed by the dramatist….

“The operations of God or of the fates must resolve perfectly, like a mathematical equation—there can be no uncathected remainder. The movements of society may be appreciated, on the other hand, as a provocative but unresolvable observation….Drama, being the less tightly structured form, allows for infinite mitigation of even its social concerns.”

· It is too rationalistic, and wholly unnecessary, to attempt an absolute schema of all the genres that stories fall into. The best scholarly discussion of genre: Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism. Best popular discussion: Robert McKee, Story.

3. Which Means That Every Writer is a “Genre Writer”

· The question is not so much whether you’re going to be a genre writer, but which genre (or mashup of genres) you’re going to choose, and how “high” your “concept” (story premise) will be.

· “High concept” (whether Crime & Punishment or Mission Impossible) means a story that is action-oriented + big risk for (an often unusual) protagonist + compelling setting + a certain amount of spectacle.

· But even minimalist, anti-plot stories have, by now, established their own genre, or form.

4. A Writer Must Master His or Her Genre

“[The writer] must not only fulfill audience anticipations, or risk their confusion and disappointment, but he must lead their expectations to fresh, unexpected moments, or risk boring them. This two-handed trick is impossible without a knowledge of genre that surpasses the audience’s” Robert McKee on genre (Story, 80).

· Love of one’s genre is an enduring source of inspiration.

· More fun with genres, sub-genres, tropes: tvtropes.org.

BONUS! The Genre of The Good Death of Kate Montclair

Master Genre: A mashup of drama + comedy (comedy indicated, among other ways, by the “mythological method” of imaging Kate’s story as a Dantescan journey through Hell into Purgatory; see especially the subtitles for the main sections of the book. For “mythological method,” see T.S. Eliot’s essay on Joyce, “Ulysses, Order, and Myth.”)

Genre of the Central Plot: Crime + Education/Redemption Plot

Genre of the Kate/Miranda Subplot: Maturation (Coming-of-Age) Plot

Genre of the Kate/Benedict Subplot: Romance

Definitely going to check this script book out! I just finished "Watership Down" for the first time ever, and never has a story made me zoom out and start analyzing the craft of writing in that way before—which surprised me to no end because adventuring rabbits are the last subject in the world to which I am drawn. Anyway, it made me want to do a deep dive into story structure, and this sounds like a perfect book to start with.

What humbling responses to your reading. That sounds breathtaking.