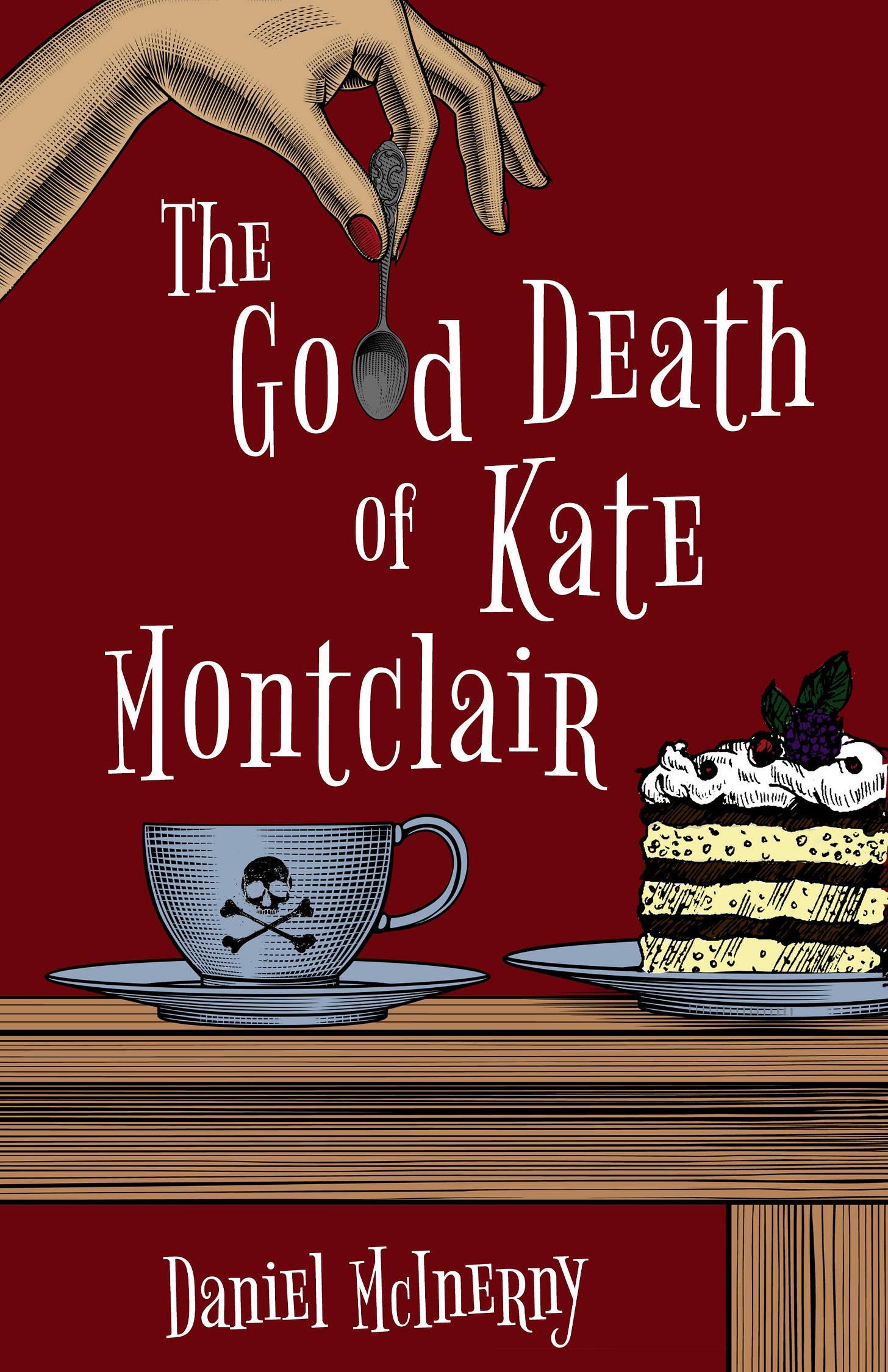

THE GOOD DEATH OF KATE MONTCLAIR

Enjoy the following excerpt from my novel, The Good Death of Kate Montclair (Chrism Press, 2023). If you’d like to read the rest, you can purchase the book here or here.

PART ONE: MIDWAY THROUGH THE JOURNEY OF OUR LIFE

CHAPTER ONE

We awaited news of my fate in Dr. Brawny Ladd’s hobbit-sized examining room. Dr. Brawny Ladd is my neuro-oncologist at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. Or he was until recently, when I retired him. His real name is Dr. Gregory Ladd, but Lisa and I call him Dr. Brawny Ladd because he’s cute and seems to be no stranger to the gym. Lisa is my good friend from school. She teaches in Brook Farm’s art department. She was with me for moral support, though only via Zoom due to the hospital’s COVID restrictions.

When he arrived in the examining room, all masked up like me, Dr. Brawny Ladd took the chair from behind the tiny desk and sat down right in front of me—so close, in fact, that the sexual energy, at least on my end, crackled to life. Amazing, that even in my parlous state, my biochemistry yearned for pleasure and connection, and above all the hope of security within this virtual stranger’s brawny embrace. But how unsuited are our needs to this world. A world where there exists bone cancer in children. Which is heated by a sun scheduled to die in a few billion years. A world with tsunamis, hurricanes, and droughts, not to mention our newest friend, COVID-19. A world in time, with a past that cannot be undone. All our mistakes set forever in metaphysical concrete.

As his voice slid down his throat and he looked with grave interest at the poster on the back of his door for the previous year’s Glioblastoma Awareness Day, Dr. Brawny Ladd lowered the boom about my biopsy. And before I was even sure I had heard him correctly, he downshifted into full masculine technician mode. “Let’s Attack the Problem!” Not with surgery, for he agreed with his even more esteemed colleague Dr. Chakrabarti that the insidiousness with which the tumor had wrapped itself around the tissues of my brain ruled that out, but with chemo and radiation that, he hoped, would shrink the tumor and allow for “a longer period of acceptable to perhaps even excellent functioning.”

But I was not really listening. As soon as I was sure I had heard him say “Glioblastoma Multiforme Stage IV” (those spiky Roman numerals are like nails in the lid of the coffin) I was gone, wondering if I would lose my hair (the hair first, always), about what I would do with Five Hearths, about the timing of my resignation from school, about how I would finance a burial plot, about whether cremation would be cheaper, about whether anyone besides Lisa and Evie and Everett and a handful of former students would miss me. I was thinking, too, of a good headline for my obituary:

Kate Montclair, Who Was Never Able to Come to Terms with Life in a Cosmos Ill-Suited to Her Aspirations, Loves, and Heartfelt Demands for Meaning, Is Cut Down by the Hand of Said Cosmos, Cruelly Below the Median Age of Death for a Person of Her Gender and Demographic Status, at 55

Or maybe 56, if I made it past my next birthday.

Eventually, dear, dreamy, ever-so-proactive Dr. Brawny Ladd picked up on the fact that, even though Lisa was fully engaged from my laptop, I had checked out. He stopped and defaulted to the first, perhaps only, talking point he remembered from Bedside Manner 101. He asked if I had any questions.

Just two. Why would a good God, supposing for the moment one exists, allow such a rotten thing to happen to such a sweet gal in the prime of life? And second, Dr. Brawny Ladd, given that I don’t see a ring on your finger, how would you like to take a dying woman to dinner? You won’t have to worry about a long-term commitment!

The question I voiced was far more prosaic, not to say dull-witted.

“So, I’m really dying?”

Poor Dr. Brawny Ladd. I had forced him to lay down his technician’s arms and address me like a human being. With those big brown eyes, he gave me a sad “You got me” look and nodded. He was so forlorn. I wanted to hug him and tell him everything was going to be all right.

“I have fifteen months, more or less,” I said. “That’s what I’ve read.”

“Every case is different,” he replied. “We’re not done fighting yet. We haven’t even started.”

“That’s right,” Lisa echoed.

“What can I expect?” I said. “I mean, what’s my life going to be like?”

“Pain will increase, but we’ll be able to neutralize it pretty well with medication. But you may experience more headaches, weakness, memory loss. Oftentimes patients experience problems with speech. But we’re going to put together a game plan.”

A game plan. Rah rah sis boom bah. Like it’s halftime of the big game and we’re 21 points down. I smiled back at him, appreciative of the sentiment but in no mood for fantasy. He pressed on.

“There’s also something called fractionated radiosurgery. Sometimes called a cyberknife. For patients with inoperable GBM’s, we’ve had some success with a three-times daily RT.” (The Brawny Ladd loved his acronyms.) “The idea is to slow the tumor’s rate of growth so as to extend the patient prognosis as long as possible. We’d give you the three doses of radiation about four hours apart.”

I replied, somewhat non-technically, “You’d zap me three times a day? How often would I have to do this?”

“Five days a week. Our RT lounge is very comfortable.”

“Five days a week? Does your RT lounge offer hot rocks massages? Free liquor? How many weeks am I supposed to do this?”

“The protocol typically runs between six and seven weeks.”

I tell you, if Dr. Brawny Ladd weren’t so gosh-darned cute when he’s in full black-ops mode, I would have laughed him out of that examining room. Six to seven weeks of thrice-daily zappings! He was like a little boy with a new water pistol; he just needed to shoot his radiation gun at something. I almost said yes because I knew it would make him so happy.

“How much more time would the cyberthingy give me?”

“For a small percentage of patients, the procedure has given them years.”

“But for most?”

“Several more months, perhaps. Some months.”

When school ends in June, and I know I have “some months” of freedom ahead of me, I am giddy with anticipation. A few summer months is a new world, rich and varied in alluring possibility. But “some months” tacked on to the end of a miserable slog through a fatal illness is a black hole of nothingness. A senseless prolongation of the awful inevitable.

“I’m not sure…”

Dr. Brawny Ladd had one more arrow in his quiver. “Some new protocols have shown some promise. There’s a clinical trial for Stage IV Glio patients going on now at the Cleveland Clinic. But it’s a Phase 1 trial—meaning that they’re still trying to figure out the right dosage of the new drug and its impact on the body.”

“How could I participate in a clinical trial in Cleveland?”

“You’d have to relocate for a time.”

“It’s bad enough having brain cancer—but in Cleveland?”

The more I listened to Dr. Brawny Ladd, the more I needed to get out of that examination room. I felt like I had been buried alive in it, with the Brawny Ladd nestled beside me ready to whisper encouraging pro-tips on how to conserve oxygen. I let him ramble for a while, but when I began to hyperventilate, I rose from my chair.

“Well, doctor, you’ve given me a lot to think about.”

“I understand,” he said. “Keep in mind that your best bet is to act quickly.”

“I just have to think—the semester just started.”

At this, Lisa nearly reached out from Zoomland to shake me. “Kate, I want you to forget about your classes. Your job right now is to focus on yourself. There’s a long-term sub policy in place for this kind of emergency.”

I knew Lisa meant this to be helpful, but I hardly found it so. Like most people, a fair amount of my identity was wrapped up in what I did for twelve to sixteen hours every day, so it was more than a little unsettling to have it ripped away so suddenly. I was a teacher. I had just started my thirty-second school year. I had lived with this rhythm almost all my life: the promise of new birth each August, the purchasing of school supplies, writing for the first time in the virgin planner, the ardent list of professional resolutions, the sheer giddiness induced by books and ideas, the newly arrived batch of fresh-scrubbed faces, some of whom I would one day count among my friends. How I loved it all, despite its many, many frustrations. Could it be possible that I had taught my final class?

“I’d just like some time to think,” I said. “This is all happening kind of—”

“Kate,” Lisa interrupted again. “Sweetie. You need to move on this.”

I brushed her off by not looking at the screen. With my eyes fixed on Dr. Brawny Ladd, I said, “Can I call you?”

No doubt he was gobsmacked by my reaction, but he didn’t break character.

“Absolutely.” He got up. “Talk to your family and we’ll make a plan.”

“Thank you, Dr. Ladd. I don’t have a family. But thank you.”

Before I even got to the elevator, I had gone through all five of Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief. Denial, anger, depression, bargaining, acceptance. She seems to have forgotten total existential bewilderment. It’s not at all the same as anger. It’s not, “I’m mad because fate is taking my life from me.” It’s more like how you feel when you watch a foreign film and you don’t get the abrupt and enigmatic ending.

Wait. That’s it? It’s over? Could someone please tell me what that was supposed to be about?

“Are you tracking me, Kate?” Lisa asked. By this point, I had made it to her car in the hospital parking lot. She was behind the wheel, and I was in the passenger seat.

“Yes,” I said.

“I don’t think you’re tracking me. That’s OK. I’m tracking for you.”

“Yes.”

“What about a second opinion? I’m calling my sister-in-law in Baltimore tonight, the nurse up at Hopkins. We’re going to get you into their cancer center.”

“I dunno, Lisa.”

“We’re not done fighting, Kate, you got that? You got that? It’s your choice how you want to proceed, but you heard the Brawny Ladd. Whatever you choose, you have to move on it.”

“Can’t I just—am I allowed to think?”

“I’m not trying to pressure you!”

“No?”

After this shot to the mouth, we went to our corners. In the stormy silence, I formulated a new plan.

“You know,” I said, “I think I’m going to take a walk.”

“A walk? OK, let’s go for a walk. Where do you want to walk to? Want to go get a drink? Want to get drunk? C’mon, let’s do it. We’ll have a late lunch and get drunk.”

“Don’t take this personally, Lisa, but I think I’d like to be alone. Do you mind?”

“I don’t want to leave you alone, sweetie.”

“I know you don’t. But I’m OK.”

“I don’t think you’re OK.”

“Well, of course I’m not OK. But I need to be alone. We introverts process differently. You’d want to talk it all out. I want to perpend.”

“Perpend?”

“Contemplate. Cogitate. Chew over.”

“Where are you going to go?”

“I have no idea. It’s a lovely day. I think I saw a notice for a shuttle to Dupont Circle. Maybe I’ll hop on the shuttle.”

“Fine. You want to be alone.”

“Thank you.”

“But I’m going to call you in two hours,” Lisa said. You’re staying in the city tonight? At the apartment?”

“Yeah. I guess. Yeah.”

“Good. I’ll call you in two hours.”

“In two hours.”

“Yes.”

“When you get home, take a big soak in the bath. Pour yourself a glass of wine. Put on Pride and Prejudice, the episode where Colin Firth strips down to his undershirt and dives into the lake. But I’m going to call you before that. In two hours.”

“Two hours.”

“I’m right here with you, sweetie. We’re going to fight this. You got that? And we’re going to win.”

As we parted, Lisa gave me a long hug and whispered, “Good thoughts, sweetie. You’ve got all my good thoughts.”

Actually, as I rode the Medstar shuttle to Dupont Circle, all I had were bouncing thoughts. Bounce, bounce, bounce. Bouncing around my mind like tennis balls.

So I will die having never accomplished with my writing what I had hoped to accomplish. Unless...unless tomorrow, while my energy is still good, I get up early and get back to that essay…

So we beat on, boats against the current.

I wonder how many essays on The Great Gatsby I’ve read in my life. Hundreds, certainly. Thousands? Practically all forgettable. Both Gatsby and I, in the end, get punished for our romantic readiness. Last spring, however, at the end of our Gatsby Unit, I finally read one that surprised me. By Alice Nwaoloko, not even one of my best students. She set the rubric emphatically aside and wrote it in the form of a diary entry by “Mrs. Daisy Gatsby,” now divorced from Tom Buchanan and the unhappy wife of Mr. Jay Gatsby. They have been living in Gatsby’s mansion in West Egg for six months, more than long enough for them to come to hate one another. While Gatsby spends his days meeting with his Presidential Exploratory Committee and visiting his new mistress, Daisy is planning a solo vacation in Tuscany in the hope of finding herself—and a hunky new love interest, just like Julia Roberts does in Eat, Pray, Love.

Is that what would have happened to us, Mr. Cody? Would you eventually have gotten sick of me, and would I have ended up as I am anyway, a catastrophist, one who repeats self-loving affirmations three times a day after meals and has had a fling or two with a hunky stranger, but who still doesn’t have a clue who she is or what anything is about?

Catastrophist (noun)

definition of catastrophist

: an exotic breed, almost entirely extinct; not a pessimist, as a pessimist anticipates bad things happening in the future; a catastrophist realizes that something horribly catastrophic has happened in the past but that most people have had the event wiped from their memories; the catastrophist’s memory was also wiped, but imperfectly, as the catastrophist remains aware that something terrible happened and that its effects remain very much with us.

As I rumbled along on the shuttle, I indulged myself in an imaginary conversation with Chloe, my therapist. “OK,” Imaginary Chloe was saying, “you’re dying. Let’s look it squarely in the eye. What feelings come to mind?”

“That it’s all been a waste.”

“What has been a waste?”

“My life.”

“Why?”

“Because nothing has come to anything. Nothing has come to a climax and resolution. I can’t even detect a narrative. It’s just a series of disconnected, for the most part unhappy, episodes. Hey! That’s Aristotle’s definition of a bad tragedy: a string of disconnected episodes. I can’t even say my life has been a good tragedy.”

“There have been disappointments,” Imaginary Chloe said. “Agreed. But surely you’ve found some satisfaction in teaching?”

“To a point, sure. There are worse things than spending your life trying to turn kids on to literature and good writing. At Christmas, kids bake me my share of cookies and mini banana bread loaves and leave me heartwarming notes along with Starbucks gift cards, so something must be working.

“But before you get all Mr. Chips on me, consider the case of Rachel Lord.

“Rachel Lord was the brightest, most gifted student I have ever taught. Period, end of discussion. You have to understand, in my classroom, written compositions can only be submitted under the following ‘affidavit’ signed by the author, a statement ending with the words:

So, acknowledging that I remain an apprentice

With still much to do on my way toward mastery

I commend this work to your discernment

Humbly requesting it be deemed acceptable

Pending the appropriate alterations.

After I grade the draft and students ‘confess’ their writing ‘sins’ to me, students are given the ‘penance’ of correcting their mistakes in a fresh draft. It is exceedingly rare for essays to go through less than three drafts. Indeed, the phrase I write on penultimate, almost-but-not-quite-ready essay drafts, ‘Acceptable, with alterations,’ has become a shibboleth among my students and always serves as the caption to my photograph in the school yearbook.

“But on two legendary occasions, a student has handed in to me, as a first draft, a perfect essay in terms of literary analysis, critical thinking, grammar, and composition—an essay requiring absolutely no alterations—and Rachel Lord was that student on both occasions. No word a lie, this kid was writing publishable poetry as a sophomore in high school. She graduated from Brook Farm and went on to get a BA in English from Harvard, then did graduate work at Cal-Berkeley. Then last week, Lisa told me that she saw an alumna’s Facebook post that said Rachel Lord had committed suicide. Overdosed on pills in a seedy hotel room in Palo Alto.

“Why, Rachel? What happened to what we used to feel when we read ‘I Heard a Fly buzz—when I died’ or The Bell Jar? What happened to the feeling that we would never be the same again, that our lives were going to burn in every moment from then on?”

Why wasn’t the poetry enough to keep the catastrophe at bay?

When I got off the air-conditioned shuttle at Dupont and was assaulted by a blast of late-August DC humidity, I realized that I was still wearing a mask. (I keep a collection of booklovers COVID masks in my purse, and all day I had been wearing the one featuring cartoons of Jane Austen’s major couples.) I ripped the mask off my face and stuffed it in my purse. If COVID wanted to kill me, it was going to have to get in line.

As I walked, it occurred to me that, when you got right down to it, death was kind of a mysterious thing.

I remembered two years ago, asleep in my childhood bedroom at Five Hearths, being awakened in the middle of the night and hearing my mother in her death delirium calling out through the darkness for her mother, long dead and deeply despised.

I remembered my friend Bianca Enderby dying of leukemia right at the start of senior year in high school. I think it’s fair to call her my friend. We weren’t super close, but we had, on two different occasions—once at a party and once in the corner of the stands at a football game—long and intense conversations about “life.” We girls all followed her final illness with fanatical melodrama, and when the news of her death was finally announced at school, we collapsed, inconsolable, into one another’s arms. Even some of the boys cried. We girls piled teddy bears around her locker. We made a pile of teddy bears that came up to our waists. Why? Why did we suddenly adopt a metaphysics that saw Bianca Enderby being ferried across the Styx comforted by 137 teddy bears? And what about Lisa’s metaphysics? What did she think “good thoughts” were going to accomplish? By sending out her “good thoughts,” did she think she was beaming into my brain tissue some special New Age healing energy?

I was thinking of people I should call. I’m an only child whose parents are deceased and who has no children of her own. Frankly, there aren’t a lot of people to call. Does one call the man one was never really married to? I can imagine that conversation.

Me: “Hi, Tim, I’m dying.”

Tim: “No problem, Kate. Because the thing is, you were already dead to me.”

No, what Tim would actually say is that he would pray for me, which would bother me even more than a snarky comment. When Mom died, he sent a condolence note saying that a Mass would be said for “the repose of her soul” at his church in Houston. I wrote back and thanked him, though I refrained from saying that when the priest came to see her in the hospital, Mom told him to get lost.

I don’t think I’ll call Tim. I don’t owe him anything anymore, not even a goodbye.

So where do you go after you learn that you have a malignant tumor growing like an asparagus bed in your brain?

My go-to place is Cool Beans near DuPont Circle, the best coffee shop in the District. During the school year, it’s where I lurk in the late afternoons to numb the pain of adolescent fumbling at composition with a dark chocolate mocha and a pastry. Something about the clean lines of the shop’s decor, the white-tiled walls, the built-in bookshelves, the gleaming silver of the espresso machines, and even the barista sporting the ski cap and the sleeve of colored tats, I find particularly comforting. I should write them an online review:

Need a place to decompress after your doc has told you that your days are numbered? Head straight to Cool Beans! The coffee and pastries are top-notch, and you can sit quietly and anonymously for hours while you ponder the meaninglessness of the indescribable physical and emotional suffering you are about to endure. Five stars!

As I walked in the door, two idle baristas, both wearing conventional hospital masks, greeted me like so many skulls with broad, blue-toothed grins. An Asian woman reading a thriller at a nearby table wore a mask, a plastic visor, and a colorful shawl swaddled around her neck.

Seating was limited to half capacity, but I still found the perfect little two-seater in the corner. I sat down with my 530-calorie dark chocolate mocha and 800-calorie pastry. Some people would want to sit and cry; all I wanted was carbs and sugar.

I had just sat down when I got a text from Lisa, a smartphone stock image of Wonder Woman flexing her bicep with a caption in all caps:

WE’RE COMING FOR YOU, CANCER!

YOU JUST MESSED WITH THE WRONG GIRL!!!!!!!!

Good ol’ Lisa. I was awful to her at the hospital. She’s just the kind of friend you want with you in a foxhole such as this. Still, it struck me that there was something a little pathetic about her kind of Never Say Die swagger. Because the truth is, I was very likely dying. And pretty soon too. The cancer cells weren’t “attacking” me in any intentional sense. They were just doing what they were supposed to do, playing their role in the general catastrophe. I didn’t begrudge Lisa the desire to fight. I really didn’t. But I would also have found it refreshing if someone went around with a T-shirt that said:

I HAVE BRAIN CANCER, AND I’LL BE CHECKING OUT BEFORE LONG

And on the back:

DID I MENTION THAT YOU’RE MORTAL TOO?

I replied to Lisa’s text by inviting her to spend the weekend with me at Five Hearths. I wanted to make it up to her, but it wasn’t just that. Usually when I lit out for my bolt-hole in Fauquier County, I was answering the call of the anchorite. I wanted nothing other than to curl up for one of my eremite weekends of reading, movie watching, cooking, bath taking, wine drinking, and compulsive journaling. This coming weekend, however, I didn’t think I could endure without some company. And Lisa knew the rule of being a good guest:

THE RULE OF ST. KATE

Article XXIV

Guests Are Allowed at Five Hearths Only If They Know How to Be Alone

and Thus Don’t Require Constant Attention,

with the Exception, Of Course, of Dinner and the Evening Movie

As I ate my pastry, I marveled at how, just a week earlier, I was in my sweltering classroom at Brook Farm, death the furthest thing from my mind. I was just beginning English I Honors Period 3. Sixteen hyperachieving first-years, all in their COVID masks sitting six feet apart, like a collection of prodigiously gifted med students. I had just begun a vivid narrative of the summer when the teenage Mary Godwin, not yet married to Percy Bysshe Shelley, traveled with the poet to the Villa Diodati on Lake Geneva, where they rented a house along with Mary’s half-sister Clare, the irrepressible Lord Byron, and Byron’s personal physician, John Polidori. Students tended to perk up when I detailed the various entanglements of free love in which this group of extraordinary young people involved themselves, and how they passed the cold, wet summer composing ghost stories, the future Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Polidori’s The Vampyre being the only two that were ever completed. But as I was telling this story, I suddenly could not remember the date of that fateful summer. It wasn’t just that I couldn’t pinpoint the year; I couldn’t remember what century I was supposed to be in. For several tormenting moments, I had nothing—as though my memory of all things Mary Shelley had been removed, like a video from YouTube, leaving only a grey screen with an unhappy face looking back at me.

Highly trained professional that I am, I began to fake my way through the lesson. For what happened next, I must rely on the eye-witness account of the ineffable Ms. Bridey Schlupp and her Rampaging Run-Ons, in which all my failures as a teacher of grammar and composition lie before me…

Bridey Schlupp

Ms. Montclair

English I Honors Period 3

August 23, 2020

For love of a task excellently done

For the love of beauty

I have put in the work

I have suffered and toiled.

With honesty I declare I have consulted the rubric

And reviewed my list of habitual errors.

With integrity I declare

this is not a first draft

And that what I submit is wholly my own.

Thus acknowledging that I remain an apprentice

With still much to do on my way toward mastery

I commend this work to your discernment

Humbly requesting it be deemed acceptable

Pending the appropriate alterations.

(signed) Bridey Schlupp

Close Observation Writing Assignment #1

Ms. Montclair’s “FrankenSeizure”

Rubric:

Word count: no fewer than 800 words

Must make observations using each of the five senses at least once

Must employ at least one good simile and one good metaphor

Must employ at least five strong verb sentence dress-ups

Must correctly employ at least five distinct vocabulary words from Vocabulary Adventure Units 1-3

So, at first we all thought Ms. Montclair was pranking us because she had just pranked us at the beginning of class. Five minutes after the bell we were all wondering where she was when she hurled [strong verb] herself out of the storage closet with cherry-colored stage blood [sense: sight] all over her face alleging [Vocabulary Adventure Unit 1] she had been attacked by Victor Frankenstein’s “creature”—still alive after all these years because he/It is “virtually immortal.” Why??? Because her father’s real name was really “Frankenstein” and the creature is out to annihilate [strong verb] all members of the House of Frankenstein including Ms. Montclair (real name: “Victoria Frankenstein”) unless she makes the creature a mate (gross!) using the physics lab here at school and the recipe her great-great grandfather bequeathed [Vocabulary Adventure Unit 1] to her. Lol!

So given Ms. Montclair’s propensity (Vocabulary Adventure, Unit 3) for classroom hijinks I don’t think us students should be very much blamed for not realizing that she was having a real seizure especially since she was just talking to us about Mary Shelley and how when writing “Frankenstein” she (Shelley) had been reading about Luigi Galvani and his nephew Giovanni Aldini and there [sic] experiments trying to bring the dead back to life using electricity otherwise known as Galvanization. Truly it was just like Ms. Montclair to roll around on the floor like she had just been galvanized. (By the way, I believe her having a seizure right after lecturing on galvanization is situational as opposed to dramatic irony because in this case, the opposite of Oedipus the King, the audience—us students—were not aware of what was happening beforehand. Do I get a bonus point???)

The first sign for me though that this wasn’t some classroom gag was when I saw little globules of foam exude [strong verb] from Ms. Montclair’s mouth like the little blobs that squirt out of the canister of Redi-Whip when it has been pretty well cleaned out [simile]. When she started foaming at the mouth, Liz Matthews screeched [strong verb/sense: hearing] and then everybody started freaking out and I experienced in my mouth the acidic backwash from my lunch [sense: taste] which is often the prelude [Vocabulary Adventure Unit 1] to hurling. It did not help that I was sitting quite near to Several Boys Who Shall Remain Nameless who had just come from P.E. and so reeked [strong verb/sense: smell] of Axe. Miraculously however I managed not to wretch [sic]. Jilly Carson meanwhile maintained a cool head as she told T.J. Stromberg to run down and get Ms. Horst, our nurse. T.J. bolted [strong verb] out the door leaving the room in pandemonium (Vocabulary Adventure, Unit 2).

Liz Matthews, the aforesaid screecher, who also suffers from a peanut allergy, then had an idea that she thought would be majorly helpful. She took out her EpiPen and stabbed Ms. Montclair in the leg [sense: touch]. It was not a bad idea but we only learned later from Ms. Horst that a severe allergic reaction is not the same thing as a seizure and so—plot twist!—the EpiPen didn’t work. Thankfully then Ms. Horst arrived and told us all to sit down and remain calm. She knelt down next to Ms. Montclair who was still shaking but not so wildly now. Ms. Horst didn’t do anything like holding Ms. Montclair down or putting something in Ms. Montclairs [sic] mouth. Liz Matthews had heard that seizure patients can choke on their own tongues and die but Ms. Horst said that was an old wife’s tale and that she should know because she is an old wife. Lol!

Soon Ms. Montclair was dead to the world [metaphor]. Then she began to snore, which totally cracked us up. Her snoring sounded like when a spoon gets caught in the garbage disposal [simile—sorry Ms. M!]. When the bell rang at the end of the period none of us wanted to leave due to acute FOMO. But when the paramedics arrived Ms. Horst told us to skedaddle to 4th period and let the paramedics do their stuff. (btw I swear one of them looked just like the dad in The Quite Place [allusion].) We were all pretty freaked out but Ms. Horst told us not to worry because Ms. Montclair was going to be just fine. Which I hope she is. Feel better, Ms. Montclair!!!

The kids told me later that I passed out, dropped right to the floor, where my arms and my legs went rigid. They described how I arched my back as though I was desperate to expel something from my mouth.

I was like this for about a minute. Then I began to convulse and emit specks of foam from my mouth. No one was timing this phase, but the kids swear my whole body was shaking for close to two minutes before the spasms began to subside. After they stopped, I lay there unconscious for several minutes. And yes, Bridey, snoring. But it could have been far worse. Based upon what I later read about seizures, I can only be grateful that I experienced no lack of control of my bladder or bowels.

When I started to come back to consciousness, I could see figures moving around, but at first they only looked like trees walking, as the man said. These were my traumatized kids flitting anxiously around me.

“Welcome back, hon.”

It was Karla Horst, our school nurse, kneeling beside me.

“Where am I?” I said. “What happened?”

“You’ve had a seizure, Kate. I called 911. The ambulance is on its way.”

I had never had a seizure before. Knew nothing about them. Karla’s voice was calm, but her hands shook as she gently rolled me onto my side and did her best to comfort me. It took a long time for the ambulance to arrive—twenty minutes, I later learned. While we waited, Karla asked me just to rest and not talk, and so I lay there assuming the worst, preparing myself for death. With unfolded laundry still on the guest room bed in my apartment. With the frying pan from my morning omelet still soaking in the sink. With the humorous essay I had been working on fitfully all summer at Five Hearths still unfinished and unfunny in the open notebook on my desk. Weird what comes to you in the final moments, or in what you take to be the final moments, of your life. I remembered, when I was twelve or so, my father returning home from a cross-country trip. He said half-jokingly to my mother about his flight home in a turbulent storm: “We were all saying the Act of Contrition.” I tried to recall it. But I ended up mumbling Grace Before Meals: “Bless us, O Lord, for these thy gifts, which we are about to receive…”

Not that it mattered. I didn’t believe there was anyone at the other end of the line, and I hadn’t since I was fourteen.

I remembered, too, looking up into a clear night sky at the morning star.

I was young and in Rome, and I was sitting on the ground holding Mr. Cody with his head in my lap and my legs weirdly splayed, like I had just attempted and miserably failed to execute one of my majestic seventh-grade splits. I had my arms around his neck and my face buried in his hair. And I said to him, “Well, Mr. Cody, look how I’m going out. On my classroom floor. I am fifty-five years old. You might not even recognize me if you saw me. Not completely gone to seed, but still, not your manic pixie dream girl anymore. Just a middle-aged lady who’s spent the last thirty years trying to learn how to deal with the catastrophe.” Little Miranda, meanwhile, was curled up beside her daddy with her head on his tummy, as though expecting him to wake any moment and roughhouse with her. I couldn’t tell her that he was dead. I didn’t know how. Where are you, little Miranda? How I’ve always wanted to find you. This, too, alas, I am going to have to leave unfinished…

As I sipped my mocha, I watched, at a right-angle to me a few tables away, two twentysomethings, their masks tucked under their chins: a tall, handsome Caucasian man with an All-American jawline, and a stunning African-American woman with high cheekbones and a megawatt smile. They were both in business attire: he in a seersucker jacket and navy-blue slacks, and she in a sleeveless pale green dress with a professional hemline right at the knee. Recent college grads, apparently, working their first big jobs in the city, indentured servants to some law firm or PR firm or think-tank. I wasn’t sure at first whether it was a date. It was possibly just a pick-me-up dose of caffeine between colleagues before they went back to work. But then he said something that made her laugh, and she looked down at her coffee, unable to handle the pressure of his gaze but basking in it nonetheless, and then I knew, perhaps better than they did, that it was a date. Nature’s wheel had begun to turn. The young had found their way into one another’s arms, little thinking about where the ride would end. What did the poet say? Birth, copulation, and death. Again and again and again.

Sometimes I feel like we’re all Londoners in 1941 who have to get up every morning and paw through the rubble of the Blitz. Except that in our case, we are all so shell-shocked that we’ve forgotten there’s even a war on. We think we’re living our best life now.

The young lovers got up to go. As they put on their masks, I had this desperate, catastrophist’s need to go over and warn them. Tell them that something had gone horribly wrong and, though I’m not sure what it was, I was sure that our masks weren’t going to help any of us.

They headed for the door. Should I run after them? At least to tell them that I was rooting for them, even though the game was rigged and they couldn’t possibly win?

But they wouldn’t understand, and how could I blame them? I couldn’t make sense of it myself.

What do you think happened, Mr. Cody? Did we do something wrong? Is this diagnosis my punishment, the final proof that I’ve never deserved to be happy? You have to help me figure this out quickly, because pretty soon your long-ago Ms. Montclair is going to return to dust.

I’m afraid I may have given you the wrong impression. This is not a cancer memoir. I loathe cancer memoirs. You know what song I can’t get out of my head whenever I think of cancer memoirs?

Johnny could only sing one note

And the note he sings was this

Ah!

The Judy Garland version, natch.

Cancer memoirs all say the same thing. That is, after they drag us through all the dreary cancer memoir tropes: the sense that Something is Not Right, the Anxious Waiting for Medical Test Results, the Grave Diagnosis, the Denial, the Rage, the Loss of Normalcy, the Loss of Hair, and Yadda Yadda, until, One Fine Day, the Cancerous Author has…an Epiphany! “Jeepers! It was Right There in Front of Me the Whole Time! How Could I Not Have Seen It? You Have to Live Every Moment. It’s a Vale of Tears, Baby, But There’s Beauty and Love and Grace If You Can Only Live Deep and Suck Out All the Marrow of Life. Every Moment: Making Scrambled Eggs for the Kids. Reading Silently with Your Partner Before Bedtime. The Smell of Coffee and All That’s Too Much for Emily Webb in Act III of Our Town. Do You See It Now? Cancer or No Cancer, You Have to Live Every Moment Like It’s Your Last!”

This, of course, is all bunk.

I mean, I’m not against a little consciousness-raising. I’m an English teacher: I can understand the value of paying attention. But the problem with living in the moment is that moments pass. In fact, logically speaking, I’m not sure it’s even possible to live in the moment. I’m straining here, trying to remember the lectures on time from the philosophy elective I took junior year. Was it Bergson? Heidegger? Anyway, what is time but the experience of a continuous flow? It’s a ride on an express, not a local. There are no stops, at least not until you get to the end of the line. And when you get to the end of the line, it’s no longer you there. It’s a corpse.

Ergo, there’s no such thing as living in the moment. There’s only a pressing of one’s face to the window of the train as the landscape whizzes by.

This is not a cancer memoir. So what is it? A Confessions? That would imply there is someone to confess to.

On the most basic level, this is the book Adele asked me to write. “You’re under the cosh, darling. I know it’s not the book you’ve always dreamed of writing. But it’s the book fate has offered you. It’s the book you were meant to write.”

This is an account of my experiences in the Death Symposium and of what I have decided to do. Names, places, and dates will have to be changed if it is ever published, but I will leave that job to others. I cannot write about this experience by hiding all the identifiers under black ink like in a classified document. I’m going to name names and reveal the locations. But I will also be careful. At Adele’s request, I am keeping the laptop, when I’m not using it, in a strongbox in my bedroom closet, and no one has a key but me. And yes, I am actually going to type. I have always written by hand, have never used a computer for any piece of writing that meant anything to me. But I do not trust my strength in the coming days and weeks, and so I will type, type against the dying of the light.

What is the Death Symposium, you ask? Come with me back to the coffee shop.

The young lovers gone, the mocha and pastry dispatched, I started work on an eminently practical End-of-Life To-Do List. But my reflections were rudely intruded upon. A middle-aged woman with stalagmites of hot purple hair sat down at the table six feet from me. She was giving a lecture via cell phone, at theatrical levels of projection, to a sister or girlfriend who simply had to learn to stop being so needy around a boyfriend who clearly had no respect for her.

I did my best to ignore the lecture and go back to my list, but the woman’s voice shattered my concentration, not to mention compromised the glass windows of the coffee shop. I should have exited stage left, with a withering look in her direction, but nonconfrontational jellyfish that I am, I instead concocted a plan to use the Ladies. Then, upon my return, if she were still on the phone, I would buy another coffee and retreat with it up to the mezzanine.

On my way into the Ladies, I was arrested by a notice pinned to the bulletin board on the wall. The advertisement was printed with black lettering on white paper bordered with blood-red skeletons lined up head to toe:

The Washington, DC Death Symposium invites you to an exploration of the things that really matter. In a compassionate, confidential, and non-judgmental environment, we discuss topics that our death-denying culture has sadly made taboo.

What song would you like at your funeral?

Describe what a “peaceful” death means for you.

How do you prepare for death and dying?

Who gets your collection of garden gnomes when you’re gone?

And did we mention tea and cake?

Coming to you every first Thursday of the month at 7:30 p.m. Cool Beans Coffee, 732 P Street NW (off Dupont Circle). Come for a frank, FUN discussion of death, dying, and what it means to be fully alive. Bring a friend, and we’ll see you there!

Meanwhile, check us out on Facebook and Instagram.

I’m not the kind of person who reads, let alone responds to, notices on bulletin boards in public spaces. Especially ones printed up like an invitation to a Halloween party. But the blood-red skeletons caught my eye, as did the name of the group: The Death Symposium, an intriguing mixture of the philosophical and macabre. The neatness of the advertisement too, the cost that must have gone into printing it—assuming these were hanging all over the District—hinted that perhaps this was not some motley collection of urban eccentrics but a group of some substance and commitment.

When I got back to my table, the stalagmite woman was quietly engrossed by her phone. I sat down, opened Facebook, and found the page I wanted: The Washington, DC Death Symposium. The stream was populated by memes with inspiring quotations, links to helpful articles about the grieving process, instructions on how to start one’s own local chapter. But I also found a link to a website. I clicked and found a well-presented page with an About tab at the top.

When I clicked on About, I came to a page presented in the form of a letter encouraging interested seekers to visit the Death Symposium. My eye tumbled down the letter as I scrolled, and at the bottom, I found a digital signature. As I read the name, not only the day’s momentous news but also the years fell away around me. It was a name that worked upon me like one of those cooking smells that transports you back to childhood.

Beneath the signature was a studio portrait of Adele herself. I had not seen her in thirteen years. She wore her sixty years with typical elegance. Her hair was now icy white, done in a pixie, and she posed with a green cape wrapped dramatically around her shoulder. She remained a strikingly beautiful woman.

“Hey! Do you know her?”

The stalagmite woman was now beside me, having invited herself right into my personal space.

“I do.” I was about to add, “We used to be very good friends,” but she blew right through me.

“Adele is fabulous. That accent! She is my favorite person in the world. Have you been to the Death Symposium? There’s a meeting next week, I think. On Thursday. Oh, you’ve got to come. I missed the last one, and I’ve been really feeling it. I know it sounds weird but just come! You’ll love it. Who would have thought talking about death could be so fun?”

No, the overall effect of stumbling upon Adele in this way was not as piquant as a cooking smell from childhood. It was more a feeling of curiosity that my life might be capable of such poetic closure, as my end joined up with my beginning.

For I did used to know Adele Schraeder. We used to be very good friends.