THE ART OF THE MEANINGFUL

The Central Problem for the Modern Artist Seeking to Work Deeply

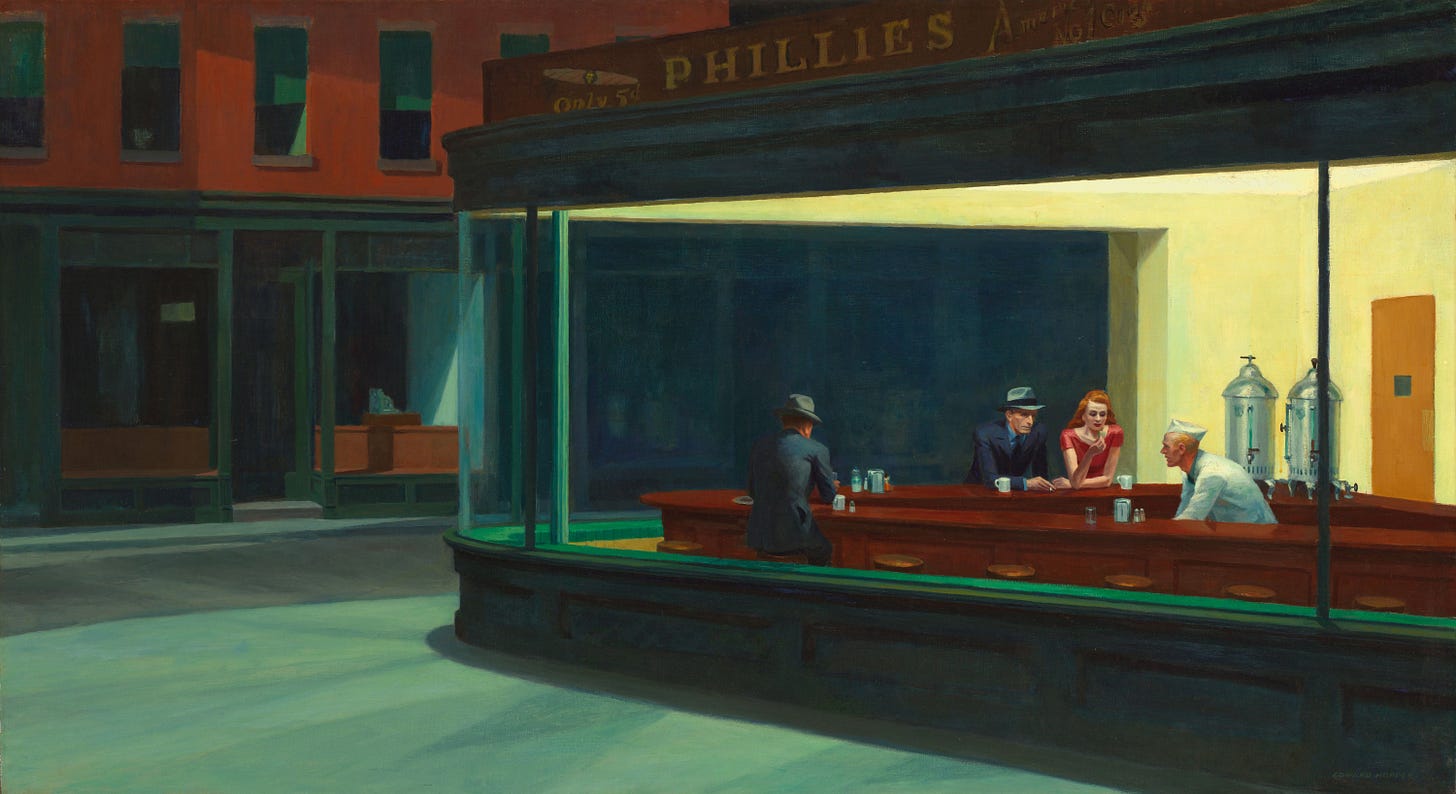

Take a look for a moment at Edward Hopper’s 1942 painting, Nighthawks. No doubt you’ve seen it before. But take another look.

Then ask yourself:

What’s up with this crowd?

I’m thinking especially of the man and woman sitting facing us at the counter.

Who goes to a diner at 2:00 a.m. to drink coffee?

And you know, that’s caffeinated coffee in those cups. In the 1940s, you didn’t go to a diner at 2:00 a.m. (in a hat and coat, in a red dress) and ask for decaf. (Sanka? Get outta here!)

Notice: no creamer on the counter, either. These two just want a cup of strong coffee and a cigarette.

Eggs Benny Goodman on toast? No thanks. Just the coffee.

The play they went to tonight at the Helen Hayes Theater on 44th Street ended hours ago. Maybe they had a late dinner afterward. Maybe they had an after-dinner drink, too.

But they still didn’t want to go home.

Wanna stop by the diner? Yeah sure.

I’m thinking: these people are trying to stay up all night.

But why?

Because they’re on the greatest date in the history of romance?

I’m doubtful.

Blow up the image and look closer. He’s just staring into space. She seems to be playing with a matchbook.

They’re not even talking to each other.

I suppose it’s possible they were chatting away with great joie de vivre just a moment ago.

But I’m doubtful.

They’re not kids, either.

Why don’t they want to go home?

I’m thinking it’s because maybe they don’t have a home.

Sure, the guy hangs that suit up somewhere. And she keeps her hair supplies and makeup in a bathroom somewhere.

But it’s not home.

About this painting, the philosopher Francis Slade has said: “It’s not just that nobody in the panting is at home. They aren’t at home—and they know it.”1

Hopper himself once said about Nighthawks: “Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”

Not just any kind of loneliness, either. But the loneliness of the peculiarly modern self lost in the modern city.

The self conceived as raw autonomy.

The self that has tasked itself to create things of compelling, lasting value—to create a life—out of his or her own meager psychic resources.

That’s a tough assignment. Who can bear it?

Not, I don’t think, our couple at the counter.

In his excellent book, Deep Work, Cal Newport tells us that deep work should be meaningful.

Hopper, however, is painting the lack of meaning. Yet this can be salutary. Such a picture can be a cleansing experience in its own right. It can allow us to look justly and unflinchingly at the world as we happen to have made it.

But what would it mean to picture meaning itself?

Before I turn to that question, let’s pause for this week’s…

McINERNY’S MUSINGS

On my bedside table, among many other books, is John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War. I’m told it is one of the very best books on Tolkien. Enjoying it immensely so far.

I’ve been thinking about the difference between Secondary World fantasy (e.g. Tolkien’s Middle Earth) and metaphysical fantasy. The pursuit of the latter has led me to fiction with a contemporary, realistic setting but which introduces fantastic, metaphysical elements: such as Muriel Spark’s The Hothouse by the East River and the very strange Charles Williams’ Descent into Hell.

At my philosophical workbench, I’ve been drafting an essay on what we can learn about art from the always fascinating Iain McGilchrist’s monumental studies on brain-hemisphere difference (see his The Master and His Emissary and The Matter with Things). In short, I’m arguing that a recovery of the brain’s proper right-hemisphere dominance—the recovery advocated by McGilchrist—encourages us to go back to a pre-modern understanding of art, one theorized so well by Aristotle and Aquinas.

“Comedy makes light of what makes us humble.” (Just the odd pearl.)

Now, let’s get back to what it would mean for the artist to do more than simply, like Hopper, picture the lack of meaning.

The Shining Things Now Seem Far Away

In Deep Work Newport discusses a 2011 book by Hubert Dreyfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly, two prominent academics, All Things Shining, “which explores how notions of sacredness and meaning have evolved throughout the history of human culture.”

“They set out to reconstruct this history because they're worried about its endpoint in our current era. ‘The world used to be, in its various forms, a world of sacred, shining things,’ Dreyfus and Kelly explain early in the book. ‘The shining things now seem far away.’

“What happened between then and now? The short answer, the authors argue, is Descartes. From Descartes's skepticism came the radical belief that the individual seeking certainty trumped a God or king bestowing truth.

“The resulting Enlightenment, of course, led to the concept of human rights and freed many from oppression. But as Dreyfus and Kelly emphasize, for all its good in the political arena, in the domain of the metaphysical this thinking stripped the world of the order and sacredness essential to creating meaning. In a post-Enlightenment world we have tasked ourselves to identify what's meaningful and what's not, an exercise that can seem arbitrary and induce a creeping nihilism. ‘The Enlightenment's metaphysical embrace of the autonomous individual leads not just to a boring life,’ Dreyfus and Kelly worry; it leads almost inevitably to a nearly unlivable one.’”

The Artist’s Metaphysical Problem

Newport identifies here the central problem for the modern individual, and so for the modern artist seeking to work deeply.

It is, at bottom, a metaphysical problem.

It is the problem, in the phrase I’ve been borrowing from Walker Percy, of “ontological impoverishment.”

A poverty of being. A lack of reality.

The human psyche itself contains too little reality, too much that is mere unsatisfied longing.

A world of order and sacredness that exists beyond the individual psyche is necessary if we are going to live deeply and sub-create deeply.

Such order is not one that we can make for ourselves. Artists have been attempting that since the Romantic period, and it never ends coherently.

Mere “personal expression” leads ultimately to a world without the shining things.

To the counter at the all-night diner.

Where two autonomous individuals endure, not just boring lives, but sad, unlivable ones.

In a clean, well-lighted place, which, as Hemingway told us long ago, is filled with nothing but nada.

Read more about Hopper’s Nighthawks on this page of the Art Institute of Chicago website.

Quoted by Robert Sokolowski in the best essay I know on painting, “Visual Intelligence in Painting,” The Review of Metaphysics 59 (December 2005): 333-354.