You received this email because you subscribed to The Comic Muse, excursions in the world of art and beauty conducted by philosopher and novelist Daniel McInerny. I hope you enjoy the following piece!

“The artist examines a civilization for its dominant metaphors. His work is “popular” when he does this too unconsciously to be critical of what he finds.”

In this light, allow me to spoil the opening episode of the enjoyable new BritBox series, Ludwig.

“Ludwig” is the nom de plum of Britain’s top “puzzle setter,” the unsociable John Taylor (David Mitchell), who is drawn by his sister-in-law, Lucy (Anna Maxwell Martin), into a search for her husband and his identical twin, James, a detective chief inspector gone missing.

It’s a humorous premise, and the execution of it, in which John goes undercover as James, is often quite clever. You won’t be too surprised to learn that, in Episode 1, John puts his puzzle-setting skills to work in solving a murder.

Which is enough to illuminate the dominant metaphor exploited by Ludwig:

The detective as puzzle-solver.

The ideal intellectual act is to consider a bewildering assemblage of accidental facts and decode the hidden narrative of material cause-and-effect.

The human mind is thus like a detective. Its function is to discern patterns in apparently chaotic matter-in-motion—whether it be who killed Colonel Mustard in the Billiard Room with a candlestick, or whether it’s possible for there to have been life on exoplanet K2-18b.

The mental process John Taylor undertakes to solve the murder in Episode 1 of Ludwig is essentially no different than that of determining the speed and direction of colliding billiard balls after a player breaks to open the game.

As in most detective shows, in every episode of Ludwig there is a scene in which the camera closes in on John as he experiences a moment of insight. His expression becomes intense and his eyes search the clues swarming in his mind until, finally, they light up with discovery. Eureka! He has discovered the hidden pattern.

But—John’s insights are of a particular kind. They are limited, once again, to concatenations of material causation. In solving a murder he discovers no more than the original stroke that explains the speed and direction of certain “billiard balls” knocked around a pool table.

“The clue and chain of reasoning function, like a jigsaw puzzle, in two dimensions. The sleuth’s reconstruction of a crime works at a level of efficient causes only….”

The efficient cause, according to the philosophical terminology being used in the above quotation, is the moving cause, the cause that explains how a given material body came to be in motion. The parent is the efficient cause of the child. My hand and arm are the efficient causes of my tea mug being raised to my lips.

Notice, however: no matter how many games of Clue you play, you never find out why Professor Plum had it in for Colonel Mustard. Was the professor the colonel’s former batman in the war, who became resentful of the colonel’s affair with his mother? We’ll never know.

Similarly, John Taylor in Episode 1 of Ludwig can only declare “I have no idea” when asked for the motivation of the person he fingers for the murder. Motivation is not his business. In Episode 3, in the midst of another murder investigation, John declares flat out that he has no interest in what motivates his suspects. And when he is forced to speculate on motivation, John’s deductions become much more a matter of educated guesswork. Which isn’t at all surprising. Why?

Because motivation gets into a realm beyond matter-in-motion, beyond the world of efficient causality and into the reasons of the human heart, which do not resolve themselves into neat acrostics.

To discern what lies beyond chains of material cause-and-effect, a different kind of insight is necessary, what might be called an epiphany:

“the epiphany implies an intuitive grasp of material, formal, and final causes as well.”

The formal cause is another name for the very “form” or nature of something. “Rational animality” is the formal cause of human beings. The final cause is the end of something, end not in the chronological sense, but in the sense of fulfillment—as the fully flourishing oak tree is the final cause of the acorn.

When we have an epiphany, we see more than just matter-in-motion. We see into the natures of things (the formal cause), and we see the progress of that nature in light of that nature’s fulfillment (the final cause). In brief, an epiphany takes us into the very meaning or intelligibility of things.

Suppose you hear me making a racket in the kitchen. You yell down to ask what the heck I’m doing, and I respond by saying I’m banging the lid of a pickle jar with a spoon. I’ve given you some kind of explanation, though not a very satisfying one. I’ve explained, on the level of efficient causality, how I’m making the noise. But without saying anything about the nature of my action and the end I am trying to achieve by it, I haven’t made myself intelligible to you.

But If I say, “I’m reducing the suction between the lid and the pickle jar by banging the side of the lid with a spoon (the form or nature of my action), so that I can open the jar and enjoy a couple of pickles with my sandwich (the end or fulfillment of my action),” then I’ve made myself intelligible.

Individual human actions have meaning, are intelligible, when we discern both the nature of the action and the end for the sake of which the action was done.

What “motivates” an action, in other words, is not merely the efficient causality involved (the movement of my arm and the impact of the spoon—which by themselves don’t even explain the nature of the action, that the banging is an attempt to reduce suction)—it is ultimately the end or good we are trying to achieve by the nature of our action.

Interesting: right before John Taylor, in Episode 1 of Ludwig, realizes he might solve the murder by treating it like a puzzle, he has a panicked phone conversation with Lucy. John is a recluse. He hardly ever leaves his home in London. He’s quite comfortable in the safe world of crosswords and chess challenges, and when Lucy issues the Call to Adventure, he can barely bring himself to get into the cab she sends for him. Now he’s being asked to impersonate his brother and solve a murder. John tells Lucy he can’t do it anymore. He wants to go home:

“I can’t do this, Lucy. I don’t know how anybody ever can. I don’t know how James ever did.”

Lucy takes John to be talking about the difficulty of impersonating James. John means something deeper:

“I’m not talking about any job; I’m talking about all of it. I’m talking about just getting up in the morning and leaving the house, coming out here to this, all this: crowds and noise and buildings and offices and computers and people! Nobody seeing each other and everybody talking at once. Alarms going off and phones ringing, everybody moving around, up and down and in and out, and no order to any of it. No structure, no purpose!”

It’s an impassioned indictment of the chaos of the modern urban world. Yet it’s clear that the “order,” “structure,” and “purpose” John craves are, in his mind, to be found in reducing that chaos to a puzzle, to a pattern of efficient causality.

What John doesn’t realize is that “order,” “structure,” and “purpose” have to do with meaning and intelligibility, and thus are accessed not by the detective’s insights, but by an epiphany.

Why do I call the detective as puzzle-solver one of our culture’s dominant metaphors? Because the kind of thinking most prized in our culture, which in fact tyrannizes our culture, is scientific-technological thinking, which is precisely the kind of discernment of chains of efficient causality put on display in each episode of Ludwig, as well as, for example, in the two-dimensional intelligence of AI (or one-dimensional, since AI is only a simulacrum of original, two-dimensional thought?).

And, despite its enormous and undeniable benefits, it is our culture’s overreliance on scientific-technological thinking that helps explain the loss of meaning, the reduction of life to two-dimensionality, so many experience. (On this theme, see the illuminating work of the neuroscientist and philosopher

, and, further back, the philosophical essays of Walker Percy, Josef Pieper, and Romano Guardini.)But there is more to the metaphor of the puzzle-solving detective. Besides the limited kind of reasoning at work in puzzle-solving, there is also, typically, the detective’s neuroticism. Isn’t it strange how the modern detective, with notable exceptions like G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown and Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, is always in the grip, if not absolutely paralyzed, by an obsessive fear that creates a reality-distortion field? Detectives from Sherlock Holmes to Adrian Monk—and one might include Christie’s Hercule Poirot—all have some anxiety, depression, or other mental and emotional disorder that they must struggle against to produce their works of genius. Poor Sherlock Holmes manages his anxiety, not with the help of an alienist, but with the violin, and, at extreme moments, a seven-percent solution of cocaine.

Our culture similarly oscillates between the two conditions of the modern detective: between the aspiration to scientific-technological prowess, and the fear of a world that seems overwhelming, principally and poignantly because the meaning and intelligibility have been drained out of it by the tyranny of scientific-technological thinking.

The two conditions are intimately, and ironically, connected.

The secret life of the modern man-god is a lonely room filled with terror and sadness.

Such as Sherlock Holmes’ lonely digs on Baker Street.

And, in another part of London, Ludwig’s lonely house where he buffers his brokenness with puzzles.

**The quotations in boldfaced type are taken, believe it or not, from a book on James Joyce: Hugh Kenner’s Dublin’s Joyce (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987), 176. In Chapter 10 of Kenner’s book, “Baker Street to Eccles Street,” Kenner compares the sleuthing mind of Sherlock Holmes, restricted to chains of efficient causality, to the mind of the artist who has epiphanies into the intelligibility of things.

***See also

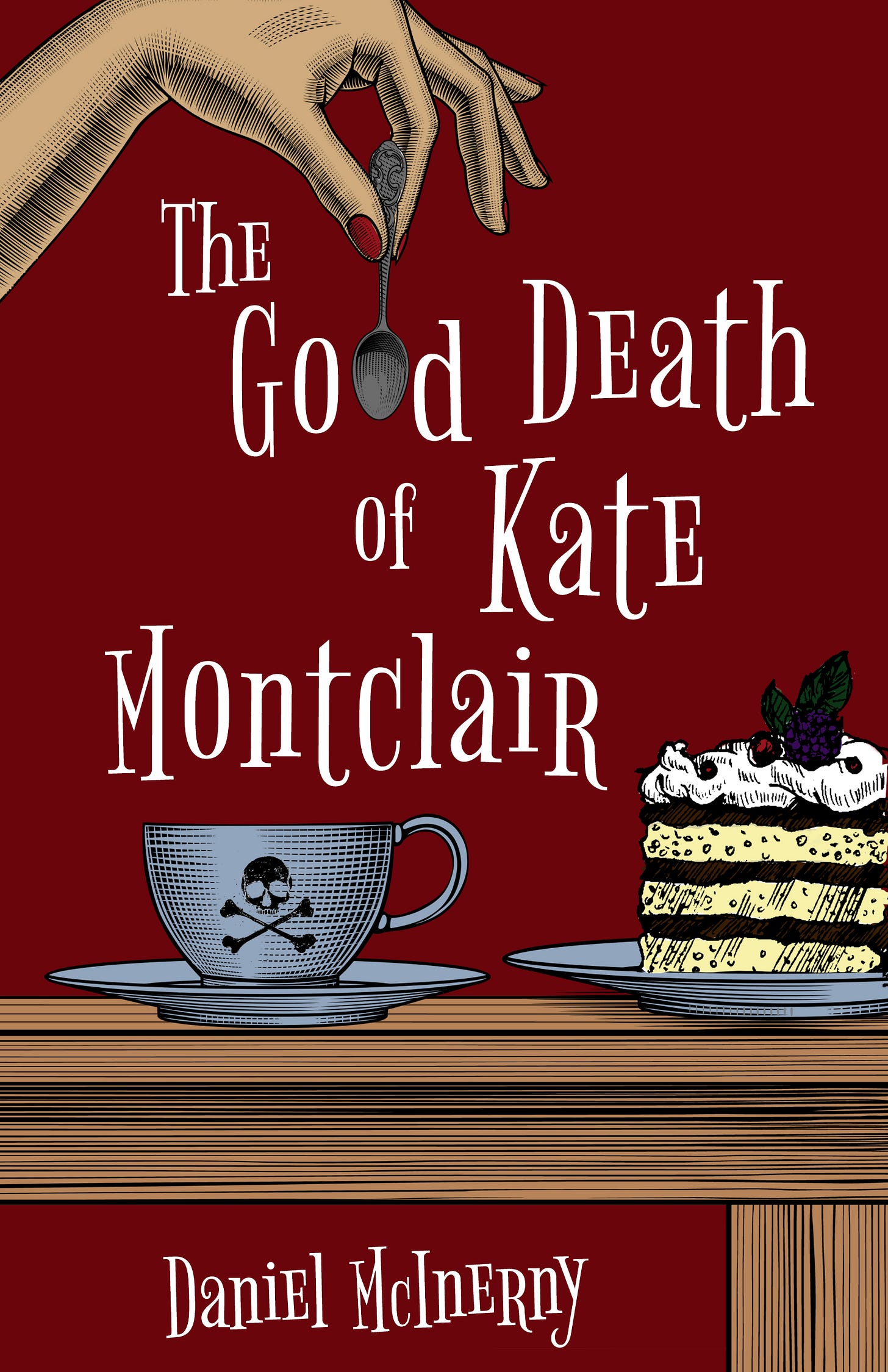

, both The Master and His Emissary and The Matter with Things; Walker Percy’s The Message in the Bottle and several of the essays in Signposts in a Strange Land; Josef Pieper’s Leisure: The Basis of Culture and The Philosophical Act; and Romano Guardini’s The End of the Modern World.I’m very grateful to April, the latest 5-Star Amazon reviewer of my novel, The Good Death of Kate Montclair:

“I have been interested in this book since it was published and for one reason or another kept putting off getting a copy. I am so glad I finally decided it was time to read this book and oh what a story!

“Friends, this book does deal with suicide, especially related to terminal illness. While that may make it a hard read, I encourage you to read it, if you can. It is powerful and thought-provoking and one I still think about frequently. I had compassion for Kate and was able to examine my own opinions and beliefs as related to my Catholic faith. A powerful experience indeed.

“There is one amazing cast of characters in this story and the slow unraveling of the past to finally meet up with the present is so well done. I truly enjoyed getting to know these characters.

“Following Kate’s story before and after her diagnosis had me thinking about how I would have handled such hard news myself.

“The secrets in this book. Oh my goodness, as the truth was revealed I was surprised and went through a whole slew of emotions depending on what happened.

“I highly recommend this book, even with the difficult subject matter. The characters and storylines are unforgettable and the messages within the story timeless.”

If April’s review has whetted your appetite for the book, you can pick up your copy by clicking here:

Professor McInerny, you've hit several nails right on the head!