Begin with the old Henny Youngman joke:

“Take my wife—please.”

It’s a classic one-liner. But think about this: you don’t laugh at it without having grasped the essential difference between two senses of the verb, to take.

On the one hand, there is take in the sense of “consider.”

On the other hand, there is take in the sense of “physically remove.”

Henny Youngman begins the joke by seeming to draw his audience into a consideration of a story about his wife: “Take my wife...” But then he yanks the rug out from under us with the single word “please,” and we realize, immediately, that Youngman doesn’t want us to just consider his wife, but to physically take her away.

Such dissection of a joke spoils comedy.

But it makes for wonderful philosophy.

For it allows us to see that even an activity as simple as getting a joke depends upon the mind’s ability to grasp essentials. We need to grasp the essential difference between the two senses of the verb to take in order to laugh at Henny Youngman’s joke.

Henny Youngman, Master of the One-Liner, 1906-1998

What Does It Mean to Grasp the Essential?

It means to grasp what must be present for something to be what it is.

To grasp what is necessary to a thing.

It is necessary to the verb to take to mean “consider.” And it is necessary to the same verb to mean “physically remove.”

Youngman’s joke plays upon these competing necessities.

The philosopher Robert Sokolowski describes the mind’s grasp of essentials in more everyday terms, as the getting the point of something.

You get the point of Youngman’s joke, you grasp what is essential to its humor, when you realize that he doesn’t mean take in the sense of “consider,” but take in the sense of “physically remove.”

Seeing More Than What the Senses Convey

Last week, with the help of Josef Pieper and St. John Henry Cardinal Newman, I spoke of the human ability to “pierce the dome” of the complacency we sink into in our workaday lives by “seeing” something that is, in Newman’s words, more than what the senses convey.

Though it might seem grandiose to say, our getting the point of Henny Youngman’s joke depends upon the mind grasping more than what the senses convey.

What happens when I hear Youngman’s joke? My sense of hearing perceives the sound of the English word take. But my hearing cannot distinguish between two senses of the verb to take. For that depends upon grasping an essential difference between two senses of the verb. I cannot grasp the meaning of to take either as “consider” or “physically remove” by hearing, seeing, smelling, touching, or tasting the word. Such grasping is the work of the mind.

Sokolowski also points out that the deeper reason we laugh at a joke like “Take my wife—please” is because such jokes tell us something essential about marital relationships.

We could argue about just what that something is: whether it is that wives are essentially aggravating, or that husbands are essentially self-serving in their constant need to feel put upon—or both.

What matters for now is the recognition that the mind is constantly at work making sense out of the world by discerning essentials.

Insight as Effortless Grasp of the Essential

But I shouldn’t say that the mind is constantly “at work” grasping essentials—because this grasping does not involve any work at all. A small child might hear Youngman’s one-liner and not “get it,” because the child is not yet familiar with the various senses of the verb to take. But an adult with a basic grasp of English will “see” or “get the point” of the joke without effort.

To put this “point” another way: the adult mind with a basic grasp of English has the insight that Youngman wants us, not to listen to a story about his wife, but to physically remove her.

But don’t let my introduction of the term insight tempt you into thinking that the grasp of essentials is something mystical or “woo woo.” It’s as ordinary as getting a joke.

Okay, having an insight is a mystical experience, in the sense that it is an act of our spiritual being (the mind, unlike the brain, is a spiritual power). But at the same time, we don’t want to make the activity of insight too otherworldly, because we’re exercising it all the time.

Like when we gaze at a painted portrait.

A good portrait, in Sokolowski’s words, “enfolds what the life unfolds.” We grasp the point of the life pictured by the portrait.

Like when we watch a movie.

A good movie provides insight into human action, allows us to “see” (in both the literal and metaphorical senses) what it means to fall in love, to act unjustly, to come face-to-face with death.

Works of the imagination are especially useful in helping us see what is essential to something, because the artist has composed his or her work with the express purpose of promoting insight on the part of the audience. Real life does not always arrange things for us as neatly as an artist does.

Insight as a Grasp of Meaning

Notice, too, that insight is always insight into the meaning of something—if only into the various meanings of an English verb. The painted portrait offers us insight into the meaning of a life. A movie offers us insight into the meaning of human action.

Insight is what allows us human beings to rise above being mere organisms-in-an-environment.

Human beings don’t just respond to stimuli in the world; we make sense out of our world by penetrating its meaning through insight.

As more than one philosopher has put it: the lower animals are in a world, but we human beings have a world. (I won’t explain that sentence further, but I bet you discern my meaning in it—through insight.)

Insight is the beating heart of all art and poetry, of all our attempts to make sense out of existence.

Insight, Human Conflict, and the Truth

And it is the only way for human conflict to be resolved and truth achieved. For only by “seeing” what is real about human flourishing can human beings discern whether their wishes, opinions, and conventional practices are adequate to what is necessary to that flourishing.

But the resolution of conflict and achievement of truth is not as simple as asking someone to just look at reality.

This is because insight is always, to a significant extent, a product of our formation. If I have no experience in watching films, I may not achieve the insight the filmmaker desires me to have. If I have been formed to think of people from another culture as second-class humans, then it will be difficult for me to “see” them as they really are.

Still, if enough pressure is put upon our misguided, conventional ways of seeing, then there is hope that we will see reality afresh.

This, again, is one of the great powers of art.

To snap us out of our complacency.

To freshen insight.

Or, in Josef Pieper’s evocative phrase, to teach us how to see again.

I’ll let Henny Youngman have the final word:

“Some people ask the secret of our long marriage. We take time to go to a restaurant two times a week. A little candlelight, dinner, soft music, dancing.

“She goes Tuesdays, I go Fridays.”

One more:

“If at first you don’t succeed, so much for skydiving.”

If you’re around the Front Royal, Virginia area, I’ll be speaking this coming Wednesday evening, September 20, at the Tolkien Conference sponsored by Christendom College in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death in 1973. My presentation is entitled “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol: Tolkien’s Philosophy of Stories.” If you can’t make it, look for the substance of my talk in my next post here on The Comic Muse.

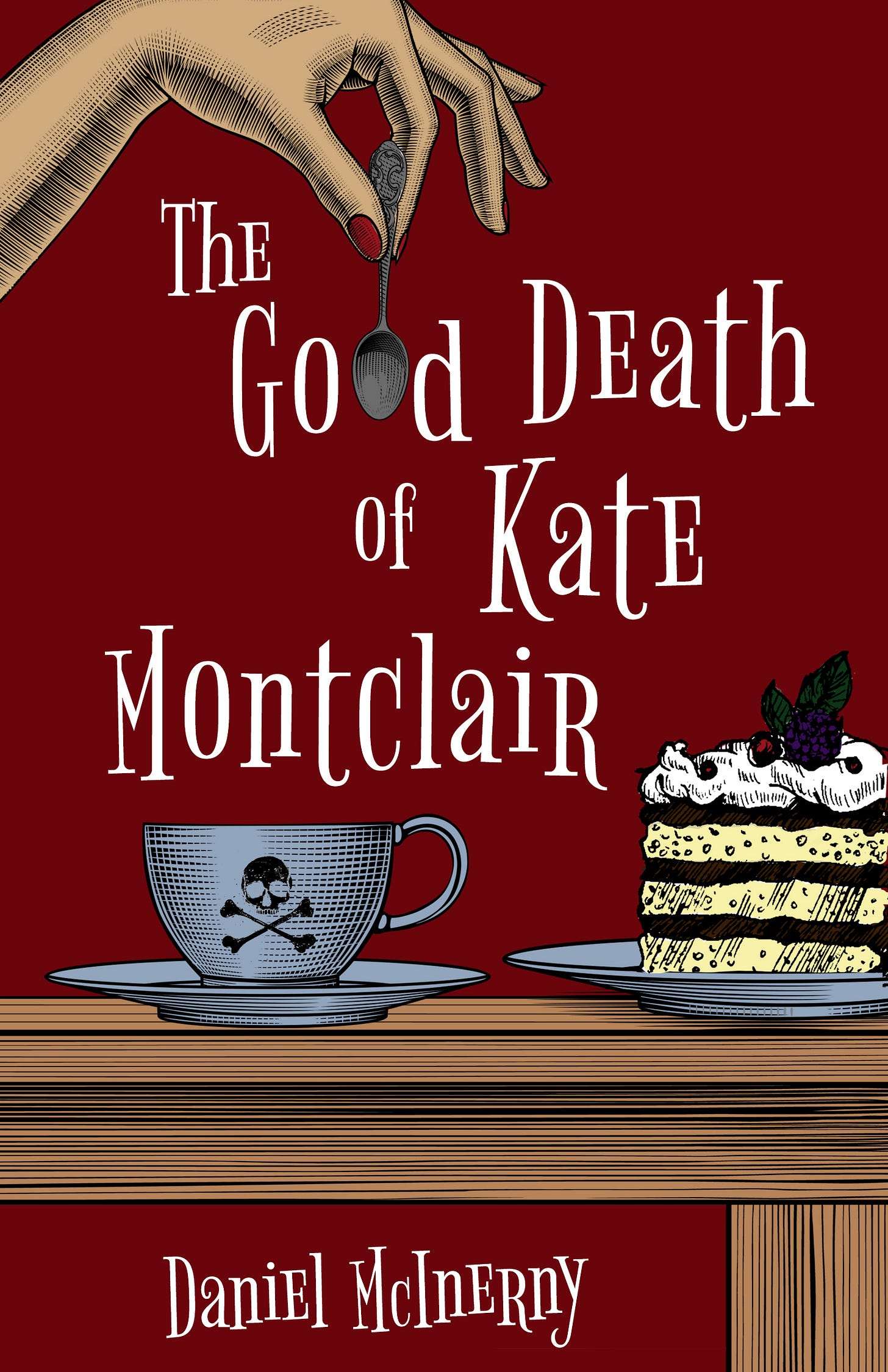

And on Saturday, October 7, as part of Christendom College’s Homecoming festivities, I’ll be giving a reading from my novel, The Good Death of Kate Montclair, as well as signing copies of the book. The reading starts at 12:15 p.m.

Here’s the latest 5-Star Amazon review of The Good Death of Kate Montclair…

“Just finished this one. Wow! A book of redemption in the modern world. The author employs his prodigious talents to interweave the past and present lives of his characters so that the reader is entirely caught up in the web of their stories, waiting for the next revelation. He presents the confusing, messy, sad, happy, frustrating, contradictory events of their lives, particularly Kate’s, which come together in a whirlwind, unputdownable ending that makes redemptive sense. The only criticism I have is that [SPOILER ALERT] Kate dies in the end.”

Pick up your copy today here on Amazon or here at Chrism Press.