Cool. But what is it?

It’s a battle for what was left, as of 1907, of Western civilization. Not as dramatic or as violent as the Somme or Dunkirk, but a battle nonetheless.

Cool. Think I can get it on a coffee mug?

Sure. Ready for the gift shop?

Totally.

While our friends visit the museum gift shop, here is this week’s

McINERNY’S MUSINGS

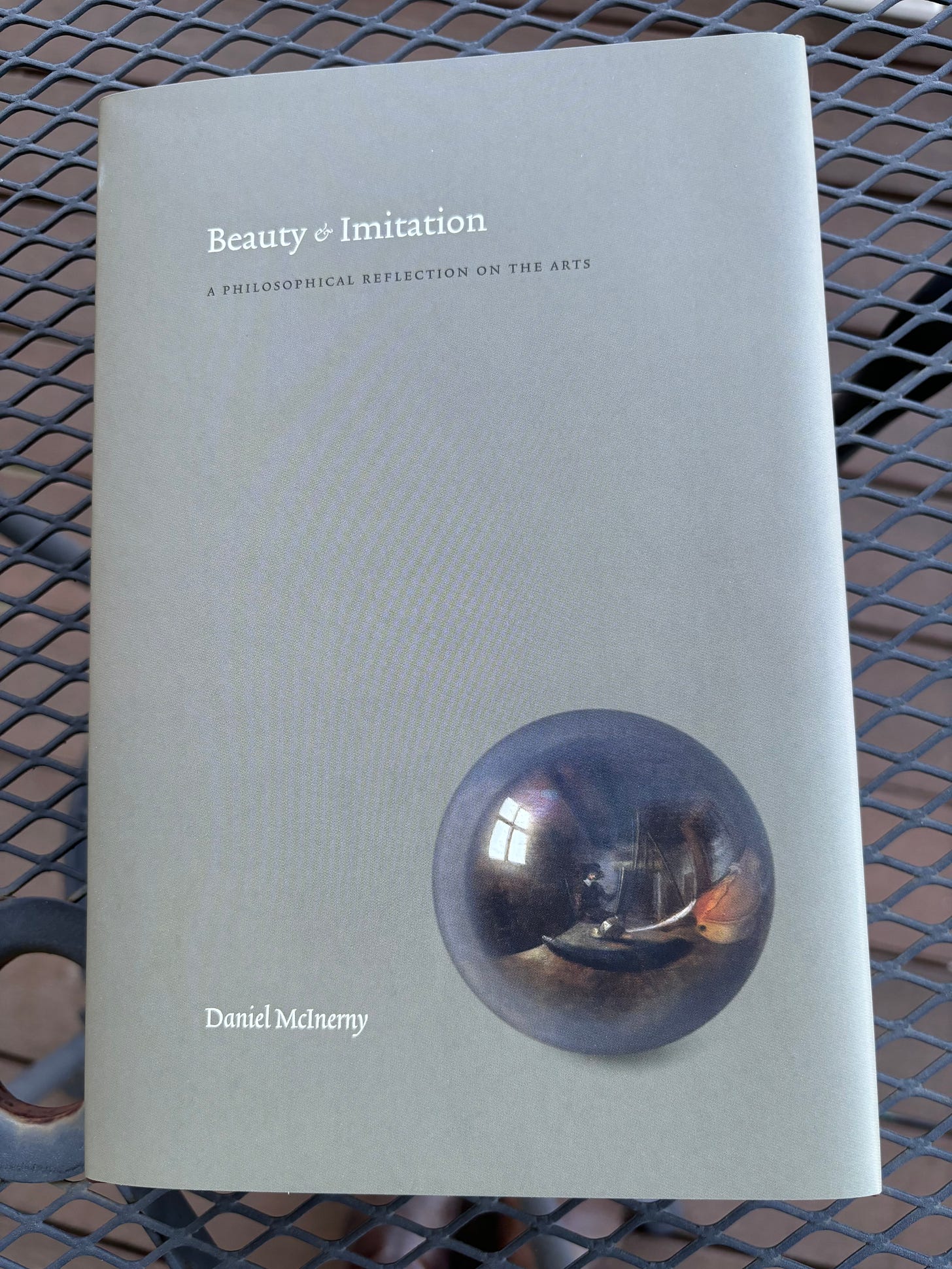

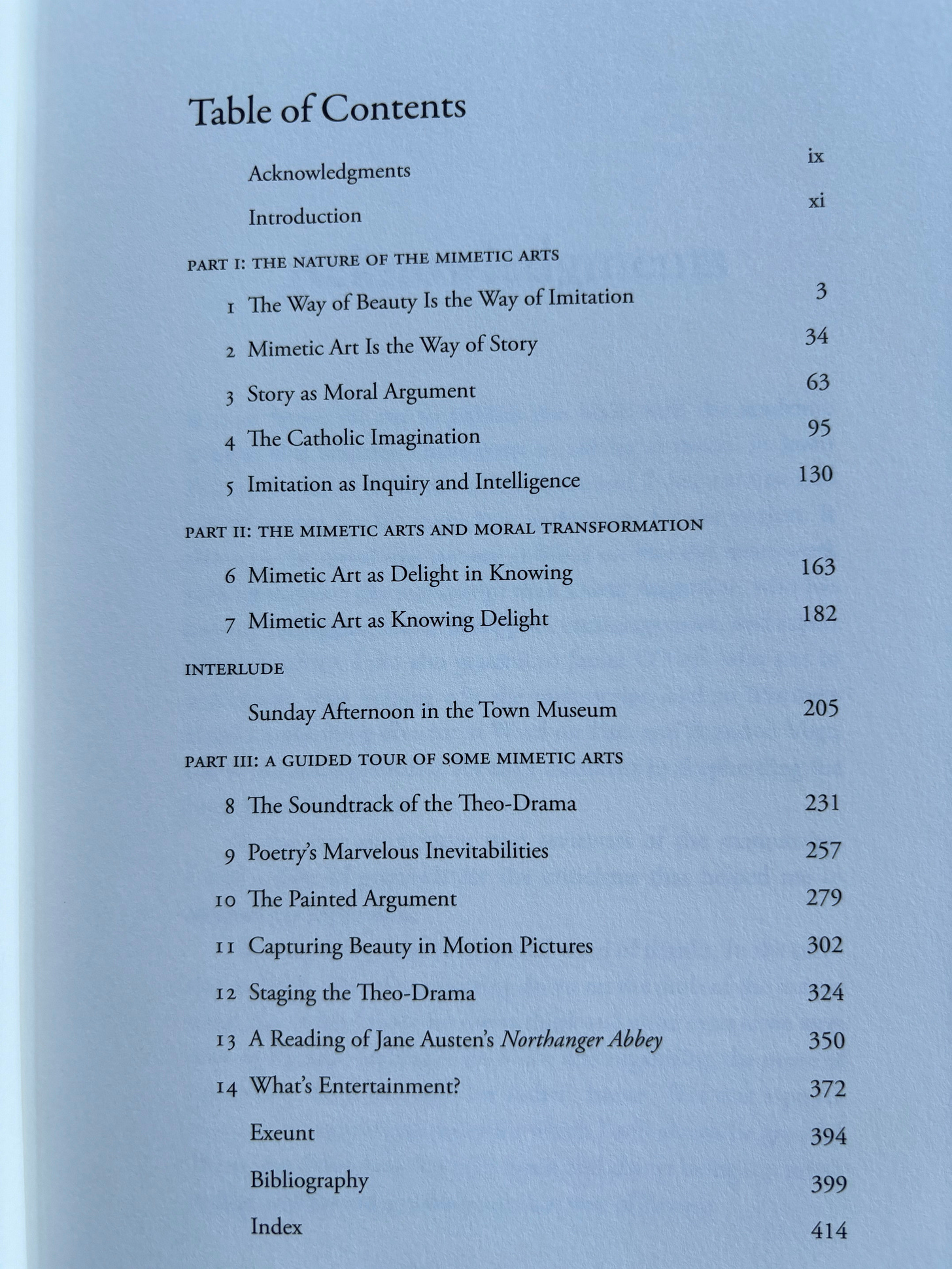

When I arrived home on Thursday evening I was delighted to find a box of author copies of my forthcoming book: Beauty & Imitation: A Philosophical Reflection on the Arts. The book will appear from Word on Fire Academic on June 3, 2024, though interested readers can pre-order on Amazon by clicking here.

In other news, we watched an unexpectedly compelling movie the other night: Surprised by Oxford. We thought it would be a conventional romance enlivened by great shots of Oxford, but it turned out to be a rather weighty story of a young woman’s journey from skepticism to faith, aided by her love interest’s robust Christianity. With great shots of Oxford. Definitely not a “deathwork” (see below).

The thought of C.S. Lewis plays a prominent role in Surprised by Oxford (whose very title, we failed to catch, is a riff on Lewis’s spiritual autobiography, Surprised by Joy). I’ve had Lewis on the mind this week, as I poached from the Christendom College “New Books” shelf Jason M. Baxter’s learned and delightful The Medieval Mind of C.S. Lewis: How Great Books Shaped a Great Mind (InterVarsity Press, 2022).

J.R.R. Tolkien also gets a mention in Surprised by Oxford, as a catalyst of Lewis’s conversion to Christianity. I’m almost finished with John Garth’s Tolkien and the Great War (Hougton Mifflin, 2003), which is a must-read for anyone interested in the sources of Tolkien’s legendarium. I like in many ways the film that was made about this part of Tolkien’s life, simply called Tolkien, but Garth’s book is so much better.

I end with a pano taken last summer of the courtyard of Magdalen College, where C.S. Lewis lived for many years while a professor at Oxford, including the years when he and Tolkien were the key players in The Inklings.

Our Lives Among the Deathworks

When it comes to the arts, we live in an age of “deathworks.”

The term “deathworks” was coined by the sociologist Philip Rieff (1922-2006) in his brilliant, difficult, absorbing book, My Life Among the Deathworks: Illustrations of the Aesthetics of Authority (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2006).

What does Rieff mean by “deathwork”?

A deathwork, he writes, is “an all-out assault upon something vital to the established culture.”

Deathworks are “battles in the war against second culture and are themselves tests of highest authority.”

To understand what Rieff is up to here, we need to distinguish between three kinds of culture:

first-world

second-world

third-world.

Do not think of the usual economic meaning of the terms “first-world,” “second-world,” and “third-world.” Reiff is creating a new typology of culture.

For Rieff, a culture is defined by its stance toward sacral order (i.e., a moral and social order established by gods or God).

“First and second worlds justify their morality by appeal to something transcendent, beyond the material world.” The shift from first to second worlds “does not disrupt the fundamental logic of culture: ethical codes are rooted in some kind of sacral order.” They can also exist simultaneously in the same society.

Third-world cultures are not technically cultures at all. They are anti-cultures. They are defined by their mission to seek out and destroy sacral order. To resist authority and subvert tradition—especially in the realms of politics, morality, and the arts. The everyday term for third-world anti-culture is progressivism.

But since first-world culture does not persist in any significant way in the 21st century, it is second-world culture—and second-world culture’s dominant religion, Christianity—that is the primary target of third-world anti-cultures.

The weapon in the battle is the deathwork.

Or, as Rieff puts it, the deathwork is the battle.

In third-world cultures there is no source of meaning or order that transcends the psychological state of what Rieff calls “psychological man,” or what I prefer to call, following Charles Taylor, the “expressive individual.”

What is the expressive individual seeking to express? His or her authenticity. For more on this theme, check out the following:

On Making Art That Will Change the World

In the 2017 film musical The Greatest Showman, about the origins of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus (starring Hugh Jackman as P.T. Barnum), there is a song called “This Is Me.” It is sung by a character named Lettie Lutz (played by Keala Settle), the “bearded lady” at Barnum’s circus. It is a stirring, defiant anthem. It begins with Lettie…

A deathwork is not necessarily a work of art. It can be a work of science. Or a cultural institution, habit, or practice.

Abortion is quite literally a deathwork.

As is the moment of silence taken before this afternoon’s “El Clasico” football match between Barcelona and Real Madrid, in which everyone in the stadium stood for a moment in honor of a deceased league official while, in lieu of communal prayer, banal ethereal music played from the loudspeakers.

What counts as an artistic deathwork?

James Joyce, Rieff contends, “is the greatest artist of deathworks, though Picasso must be a candidate for that title.”

Rieff is thinking of Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegans Wake.

About Picasso’s 1907 deathwork, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Rieff sees in it Picasso’s hope “to disarm Christian images of the world woman, the mother of the second person of highest authority, in his images of the world woman as a threatening transgressor.”

As deathwork, Rieff also cites the poetry of Wallace Stevens.

It may be questioned: Is every work of contemporary art a deathwork?

Of course not.

But: artistic deathworks are the definitive, characteristic art of the age.

Even those works which seem harmless are not necessarily so. Taylor Swift’s new album, The Tortured Poets Department, channels her expressive authenticity in yet one more iteration of the Romantic dream of liberated—and inevitably disappointed— sexual eros. Romanticism may be defined as, at once, both a third-world rejection of second-world culture and a yearning for the transcendence so rejected.

It may be asked: How did we get here?

How did the war against second-world culture come about?

I will be pursuing answers to those questions in my next post.

** The photo at the head of this post is from the pablopicasso.org website.