You have received this email because you subscribed to The Comic Muse, a review of culture and the arts by philosopher, novelist, and dramatist Daniel McInerny. I’m here to help you find the way of artistic beauty within our dark wood of anti-culture and technopoly. Thanks for joining me.

Florence’s Poor Christmas Box Office; Celebrated Creative Fra Angelico Talks His and Fra Lippo Lippi’s New “Tondo”; Cosimo de’ Medici on the Strange ROI of Sacred Art

In this LIVE episode from Florence, Kim Masters and Matt Belloni talk about the city’s poor Christmas box office—which consists quite literally of a poor box outside the Medici Palace; afterward, they sit down with Fra Giovanni Angelico (“Fra Angelico”) to talk about his and his fellow creative Fra Lippo Lippi’s new “tondo,” The Adoration of the Magi. Finally, Fra Angelico’s patron, Florentine powerbroker Cosimo de’ Medici, visits the studio to talk about the challenges of bankrolling sacred art that almost no one in Florence sees.

You Get the Joke

No one will miss the fact that there’s a joke here. That there’s an incongruity between Fra Angelico and Cosimo de’ Medici appearing on a 21st-century podcast about the business side of the entertainment industry.

But where exactly does that incongruity lie?

Besides the obvious fact that The Business podcast with Kim Masters didn’t exist in 15th-century Florence, there remains a massive difference between Fra Angelico’s artistry (and Cosimo de’ Medici’s patronage) and the contemporary entertainment industry.

But in what exactly does that difference consist?

Art as Adoration

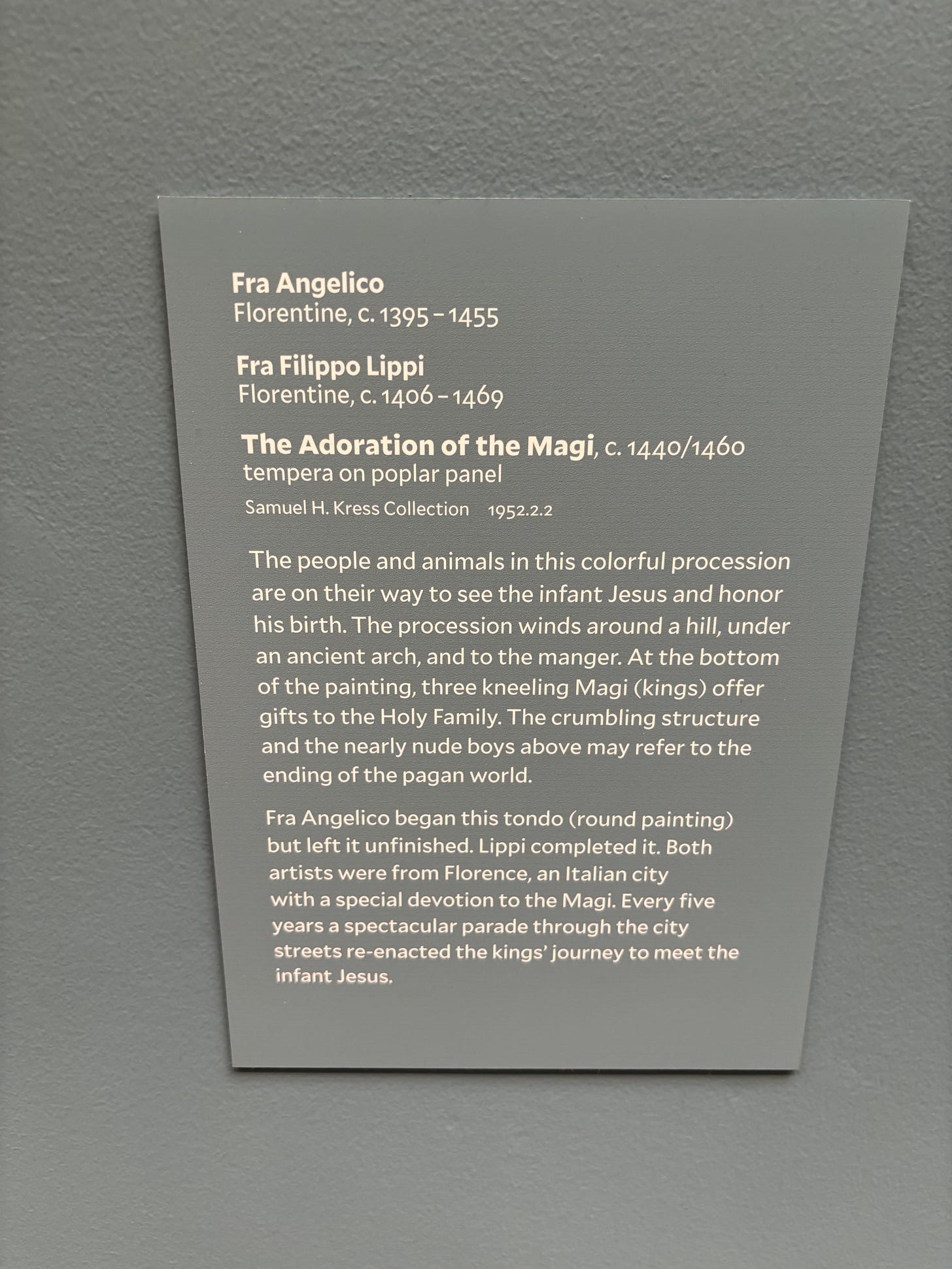

Begin with Fra Angelico’s subject matter. He and Cosimo de’ Medici were members of a vibrant Catholic culture; indeed, they were living in a city, Florence, which was one of the brightest flowers of that culture. The Medicis were known to have a special devotion to the three Magi. And so, it was only natural that Cosimo de’ Medici would commission Fra Angelico to paint a “tondo” (a circular painting) featuring the adoration of the Magi. (The painting now hangs in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. These images are from my visit to the gallery in June 2024.)

Which is to say: Fra Angelico’s The Adoration of the Magi (c. 1440/1460, completed by Fra Lippo Lippi and probably other hands) emerged organically from a religious culture. The composition of the painting itself, as well as the enjoyment of it by members of the Medici family and their friends—the tondo apparently first hung in one of the “grand rooms” on the ground floor of the Medici Palace—were also acts of adoration.

This adoration represents a chasm that exists between the world of Fra Angelico’s tondo and the world of one of the works of art recently discussed on The Business podcast: the film adaptation of the Broadway musical Wicked. Whatever its merits may or may not be, Wicked, except in the most attenuated of senses—in which one might identify the Christian origin of fairy tales like The Wizard of Oz—did not grow out of a tradition of religious practice. It is not, in any straightforward way, an act of adoration.

The Festive “Home” of Art

In his penetrating book, In Tune with the World: A Theory of Festivity, Josef Pieper argues that the arts, both in terms of their history and in terms of their nature, find their “home,” their appropriate context, within festivity.

What is festivity?

It’s more than just a party. More than any ordinary celebration.

Festivity, Pieper teaches us, means to “to live out, for some special occasion and in an uncommon manner, the universal assent to the world as a whole” (In Tune with the World, 30).

At its heart, festivity is an act of attention, a special sort of insight, in which we see that this birth, this marriage, this anniversary, this retirement, this community, is an emblem of the goodness of all that is, including, above all, the goodness of the divinity that brings all into existence.

And from this insight springs joy. And from this joy, the desire to express it: in costume, in sport, in good food and drink, in liturgy above all.

But also in the arts.

Pieper quotes Plato: the Muses, the traditional mythical sources of art, a band of goddesses which includes, of course, the Comic Muse, were given to us as “festival companions.” “And indeed,” Pieper adds, “a festival without singing, music, dancing, without visible forms of celebration, without any kind of works of art, cannot be imagined” (52).

The invisible aspect of festivity, Pieper argues, the praise of the world which lies at a festival’s innermost core, can attain a physical form, can be made perceptible to the senses, only through the medium of the arts (52-53). The arts are the perceptible manifestation of festive affirmation. Both art and festivity are nourished by affirmation of Creation (54).

Not all festivals are specifically religious, yet Pieper proclaims that there is no genuine festivity that does not include affirmation of the divine as the source of the goodness of all that is.

The implication being that there is no genuine work of art that cannot be understood as an expression of that same affirmation.

One of Pieper’s most thought-provoking claims is that the arts keep alive the memory of the true ritualistic, religious origins of festivals when these begin to wither or be forgotten (53). For many, the arts are the only pathway to realities that transcend our existence as organisms within a material environment.

Wicked Difference

Against this backdrop, we can see more clearly how Fra Angelico’s tondo is incommensurable—“not able to be measured by the same measuring stick”—with a film such as Wicked. The two works are, as we say, “apples and oranges.”

Part of this incommensurability lies in the ways in which the economic situation of The Adoration of the Magi was so different from the capitalist economy that produced Wicked. Fra Angelico needed a patron to do his work—wealth is not irrelevant to the making of art. But the patronage system is hardly equivalent to the byzantine economic machinations of the contemporary entertainment industry that brought Wicked into being. Fra Angelico did not have to worry about the “box office.” Cosimo de’ Medici did not have to worry about a (material) return on his investment.

The Adoration of the Magi was made to exist in a realm above and beyond the world of “industry.”

There is further incommensurability in the way the medieval world and the world of contemporary entertainment talk about art. It is ridiculous, for example, to refer to Fra Lippo Lippi as Fra Angelico’s fellow “creative.” This talk of people who make things as “creatives” does not belong to a permanent, transcultural language about art. This term belongs to another world than that of The Adoration of the Magi. Fra Angelico would have recognized only God as a “Creator.”

Who Cares?

Why should we, in 2024, be interested in these differences between how medieval Florentines made art and how art is produced in the contemporary entertainment industry? It’s interesting historically. But beyond that, who really cares?

We should care, first of all, because we love art. We cannot, we do not, live without it. As human beings we are made to contemplate and delight in works of art. Art nourishes our souls. So, we should care about what our souls “consume.”

And what we “consume” becomes a different kind of thing when it is placed in different contexts. The hamburger we snarf in our car in the parking lot of the fast-food restaurant becomes a different kind of thing when enjoyed amid the conversation and laughter of festival companions.

The analogy, however, is not strong enough. Because in the analogy, it is, presumably, the same burger that is eaten in the car and in the midst of festivity.

But it is not the same kind of work that is produced in medieval Florence and (typically) in contemporary Hollywood. It is totally different in kind. Apples and oranges. Or, burgers and Timbale de Riz de Veau Toulousaine (Bertie Wooster’s favorite dish as prepared by his Aunt Dahlia’s chef Anatole).

The chief question provoked by this comparison of Fra Angelico’s tondo with a film such as Wicked is whether art made outside the context of festivity is art that nourishes us.

Is it art that affirms the goodness of all that is? Or is it art that despairs of goodness?

Is it art that acknowledges our creatureliness and dependency? Or is it art that indulges fantasies of ego-aggrandizement?

Is it art that comprehends the human person as existing in an order that he does not make? Or is it art that encourages the grotesque ideal of human mastery and control over nature?

The point is not that all art must be sacred art. Festivity and art can well exist outside a liturgical context.

But the question we need to grapple with is whether the art we make today is genuinely festive in character.

Or is it positively anti-festive? Or somewhere in between?

What say you?

Great article, Daniel. Having built YouTube channels with millions of followers, I've experienced firsthand how economic pressures can transform creative work into a cycle of audience-driven content. Even at scale, we risk falling into the same trap that's led Hollywood into its endless remakes.

While we see alternative funding models emerging, from non-profits to crowdfunded projects like 'The Chosen,' the fundamental tension remains. Modern patronage might work for paintings, but what about massive undertakings like films or cathedral that require an army? Should we be developing systematic patron pipelines, or should artists become their own patrons? I think of 'The Passion of the Christ' – a profound work of art that emerged from our profit-driven system, suggesting some possibility of reconciliation between artistic integrity and commercial viability.

As someone straddling both creative and business aspects of media, I'd love to hear your thoughts on navigating this dynamic.