Flannery O'Connor on the Judgment of the Novelist

Or, why this newsletter is called THE COMIC MUSE

Welcome to the many subscribers who have joined us here at THE COMIC MUSE in recent days. As far as I can tell, you found us because the Substack of our good friends at 100 Movies Every Catholic Should See was featured in the Catholic Vote daily email, and THE COMIC MUSE is first among the recommendations at the 100 Movies Substack. In any event, welcome to one and all! Have a look around at your leisure.

And if you like what you find here, I hope you will consider becoming a paid subscriber. For just about the cost of an Americano per month, you can support both my efforts to practice the craft of fiction with consummate skill, and my philosophical reflections upon that craft, and indeed about upon all the arts, toward the end of revivifying them for our desperately joyless age.

Find out about my novel, The Good Death of Kate Montclair (Chrism Press, 2023) here. And discover my latest work on the philosophy of art, Beauty & Imitation: A Philosophical Reflection on the Arts (Word on Fire Academic, 2024) here.

Next Tuesday, March 25, 2005, the Feast of the Annunciation, marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of one of the greatest writers of the 20th century: Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964).

Last week I visited Andalusia, the farm in Milledgeville, Georgia where O’Connor spent the last 13 years of her life living with her mother. I also did some work in her archives at nearby Georgia College & State University (where O’Connor attended in the 1940s, when it was called Georgia State College for Women).

On Tuesday, in celebration of O’Connor’s birthday, I will post more pictures from my tour of Andalusia. Today, I’d simply like to share one gem from the many writings of O’Connor I poured over last week.

This one is from an interview she gave to an unidentified source, sometime later than May 1961 (and so toward the end of her life). I asked the chief archivist why O’Connor would have a typescript of this interview. The chief archivist’s surmise was that O’Connor, perhaps because she was frail from lupus at this time, probably preferred to conduct the interview by replying to a set of written questions.

Here is the passage that struck me so much that I copied it out.

“I think the novelist does more than just show us how a man feels. I think he also makes a judgment on the value of that feeling. It may not be an overt judgment. Probably it will be sunk in the work but it is there because in the good novel, judgment is not separated from vision.”

O’Connor’s philosophy of art, we see here, does not value emotional expression for its own sake. The emotion that the artist endeavors to “sink” into the work is only interesting and valuable, for both artist and audience, if the emotion is shown, as it were, “under judgment.”

The work of art “makes a judgment on the value of that feeling.”

This puts O’Connor’s understanding of art at odds with much thinking about art today.

It also provides a succinct gloss on why I call this newsletter THE COMIC MUSE. For art made in the spirit of the comic muse is always aimed at picturing some aspect of the human quest for the good, for fulfillment, a quest which focuses the artist’s vision, and provides the basis for the artist’s judgment on what he or she is picturing, including the emotional content of the work.

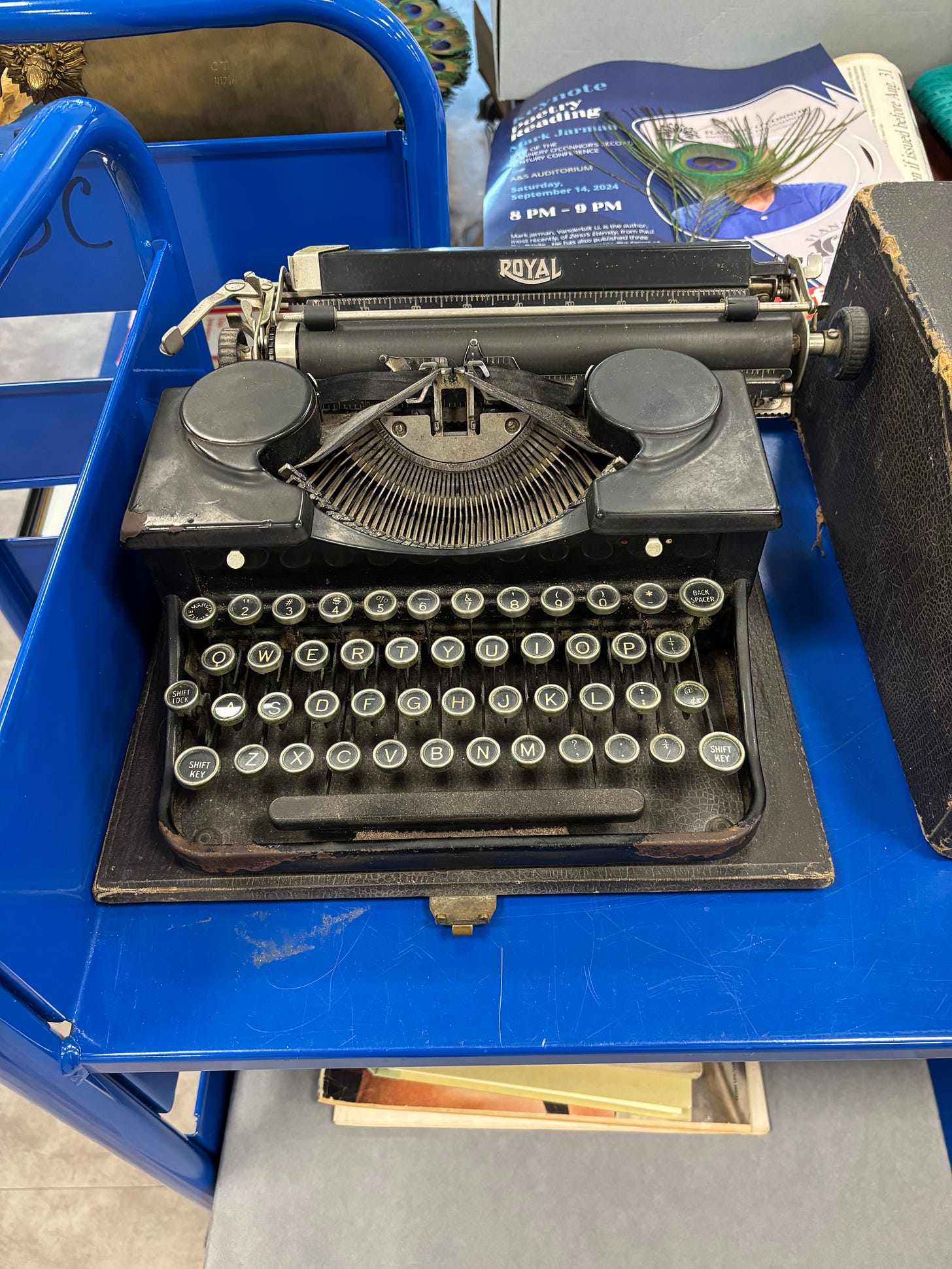

One of Flannery O’Connor’s Royal typewriters

A related post on Flannery O’Connor…

A Meditation on Wildcat in 17 Scenes

The following is not a review of Ethan Hawke’s Wildcat, a film about Flannery O’Connor’s creative, spiritual, and physical struggles as a young writer. But I am happy to say I very much enjoyed the film. Hollywood might make more films like this, if it had been somebody there to shoot it every minute of its life.

I imagine the aim of the novelist is for the reader to have an understanding/sympathy of the protagonist, but not overly identify with them if they are pursuing something reckless that will lead to their destruction. Does that make sense? Sometimes I find myself 'rooting' for a character, as it were, and then they do something that I just can't swallow morally/ethically speaking. The novelist likely has this in mind as they're writing, and that makes it all the more daunting a task to write good literature. Or perhaps that's not what Flannery is saying here. I'll have to think on this...