BABY YODA & THE MONEYCHANGERS

Why the human spirit languishes when art becomes product

This post is free to all readers, but if you’d like to support my work here at The Comic Muse, and so enjoy unlimited access to all posts in the

STARVING ARTISTS 101

The Comic Muse Academy Proudly Presents… STARVING ARTISTS 101 A Workshop for Ontologically Impoverished Creatives Instructor: Dr. Daniel McInerny Time & Location: regularly at danielmcinerny.substack.com Spring 2024 COURSE SYNOPSIS The aim of this workshop is to awaken artists, art lovers, and miscellaneous “creatives” to the possibility of their ontological impoverishment. What is “ontological impoverishment”? Simply: a paucity of being (

STARVING ARTISTS 101 workshop, then please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

“They are products, not stories.”

Such was the lament of one young man at what Disney has done with the character colloquially known as “Baby Yoda” (the character’s name is actually Din Grogu), who appears on the Disney+ shows The Mandalorian and The Book of Boba Fett.[1]

“The point is not that Star Wars spinoffs are inherently bad,” said the young man. “The first two seasons of The Mandalorian were fun, Star Wars-worthy fare. The second season even came to a magical climax when [BIG SPOILER WARNING] Luke Skywalker appears with R2-D2 and the Mandalorian gives Baby Yoda permission to depart with them to complete his Jedi training.

“But after that, Baby Yoda and the Mandalorian reunited on another Disney+ show, The Book of Boba Fett, which allowed them to reappear together—without explanation, banking on the audience’s familiarity with Boba Fett—back on The Mandalorian.

“The problem,” said the young man, “is that these tortured plot-moves were not made for the sake of developing a character as he quests for his goal, a character with whom we can forge an emotional connection. They were made to sell you the Disney+ subscription service, a video game, or a Baby Yoda plush toy.

“Disney realized that they couldn’t have a financially successful show in The Mandalorian without Baby Yoda, so they simply, but unpersuasively, concocted a way to bring him back.”

We shouldn’t be surprised, then, that at Disney’s first-quarter earnings conference call back in February, CEO Bob Iger announced that a new Star Wars movie was being developed “that brings the Mandalorian and Grogu to the big screen for the very first time.”[2]

QUESTION: Why is our young man so demoralized by what Disney has done with Baby Yoda?

(a) Because he’s sick and tired of Disney’s egregiously lame acts of product placement.

(b) Because on the first episode of Season 3 of The Mandalorian, there was no explanation of why Baby Yoda was back. Disney just assumed the audience would know what happened on The Book of Boba Fett. But Boba Fett was a notoriously bad show which no one watched, and so the return of Baby Yoda on The Mandalorian came to most people as a massive shock.

(c) Because after Baby Yoda blew up the internet in 2019-20, the young man cannot bear anymore to look at that doe-eyed, hairy-eared, little green furball and all of his attendant memes.

(d) It has to do with the importance of myth to art and to human life. Star Wars is important because it offers, at its best, and with no little humor, panache, and excitement, what all good myths offer: a picture of forces of good aligned against forces of evil; of heroism; of an understanding of human existence that transcends the immanent life of a mere organism-in-an-environment (where we satisfy our daily needs, grasp at more than those daily needs, and nurse our ego’s sense of entitlement). To trade-in that offer of transcendence for a chance to sell a few more plush toys is a degradation of art in general and Star Wars in particular, and so it is no wonder that so many fans are left demoralized.

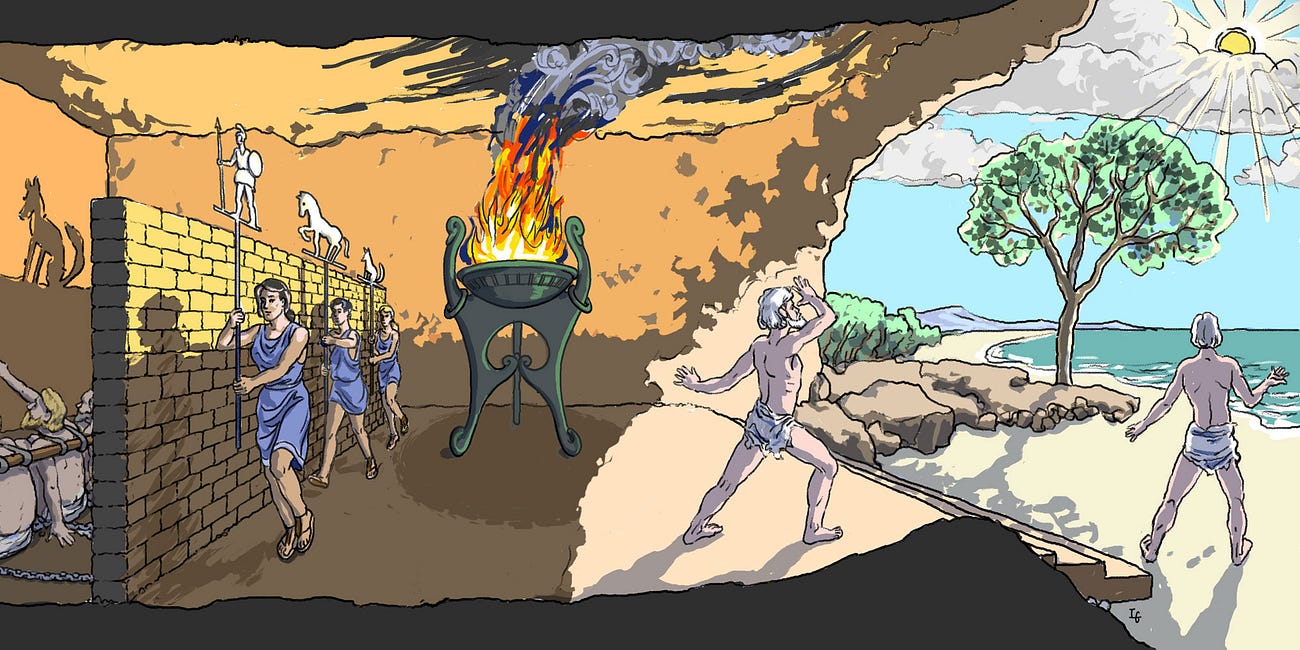

Myth is crucial nourishment to the human spirit because it takes us beyond the mere facts of our immanent existence. Living as a mere organism-in-an-environment frustrates our spiritual impulses. St. Thomas Aquinas says that the human intellect is made for “universal truth” and that the human will is made for “universal good.” By “universal truth” St. Thomas means all truth, complete truth. And by “universal good” he means that which is all good, good without qualification. But the implication is that “universal truth” and “universal good” cannot be found anywhere in the created world, where truth and goodness are always limited, finite, compromised. Universal truth and universal goodness are literally “out of this created universe.” Ultimately, they can only be realized in God.[3]

Our spirits yearn for the transcendent realities of truth and goodness, and myth promises a picture of those realities.[4] But when our stories become products, they keep us tethered to our immanent existence. As opposed to showing us what life might look like beyond immanence, they only offer us one more opportunity to consume and be titillated by something, and so assuage, yet only for a moment, the ego’s need to fill up its emptiness.

Once upon a time, when Jesus went up to Jerusalem for the Passover, “he found people selling cattle, sheep, and doves, and the money changers seated at their tables (John 2:13-14). He proceeds to make a whip of cords and drive them out. I take this as an image of what storytellers and other artists need to do with those who would reduce stories, and especially myths, to products. When the Pharisees, stuck in the immanent mindset, ask Jesus, “What sign can you show us for doing this?”, Jesus replies: “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.”

Notice that Jesus does not respond to the Pharisees on a literal level (although they take his response on the literal level). Jesus doesn’t say, “Because I am God, and I have authority over what goes in the temple.” Rather, he gives them a metaphor, which is the seed of myth. He refers to himself as the “temple.” He invites the Pharisees to think of him in a “right-hemisphere mode” (the metaphorical, mythmaking mode), rather than in the literal, “left-hemisphere mode.”

And so, on my analogy, should art invite us to transcend immanence.

[1] This young man looked and sounded, curiously enough, like my son Francis. To his help with this post I am greatly indebted.

[2] “Walt Disney Company Q1 FY24 Earnings Conference Call,” Walt Disney Company, February 7, 2024, as quoted on the Wikipedia page for “Din Grogu.”

[3] Summa theologiae I-II, question 2, article 8. “Obiectum autem voluntatis, quae est appetitus humanus, est universale bonum; sicut obiectum intellectus est universale verum.”

[4] Bob Iger’s instinct to ramify the Star Wars myth is not wholly mercenary. Myth by its very nature is made to branch out, to cover more and more of the “universal.” In his letter to Milton Waldman (1951), J.R.R. Tolkien explained that he once “had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy-story—the larger founded on the lesser in contact with the earth, the lesser drawing splendor from the vast backcloths….” As quoted at the beginning of Christopher Tolkien’s edition of The Silmarillion, 2nd edition (New York: HarperCollinsPublishers, 1999), xii. With the help of his son, Tolkien succeeded in his ambition very well.

*** The photo of Baby Yoda above, by Lskbrown, is used under the Creative Commons License 3.0. It is available at Wikimedia.com.

Very interesting any insightful, thank you.