Donegal…Dublin…Birmingham (UK)

We stayed the Monday night of August 7, 2023 at the charming and happily non-touristy Caisleáin Óir Hotel in Annagry, County Donegal, so that we could get to the nearby Donegal airport early the next morning for our flight to Dublin. The hotel staff was kind enough to bring us a pot of tea and brown bread while we waited in the lobby for Josie (Joseph), our taxi driver, who had also brought us to the hotel the afternoon before, after we had said goodbye to our friends from Christendom College.

Dublin was only a stopover to change flights. From there we journeyed on to Birmingham, England, a not terribly attractive industrial city right in the middle of the country. Why? Because at 4:00 p.m. that afternoon of August 8 we had an appointment at the Birmingham Oratory to see the Cardinal Newman museum.

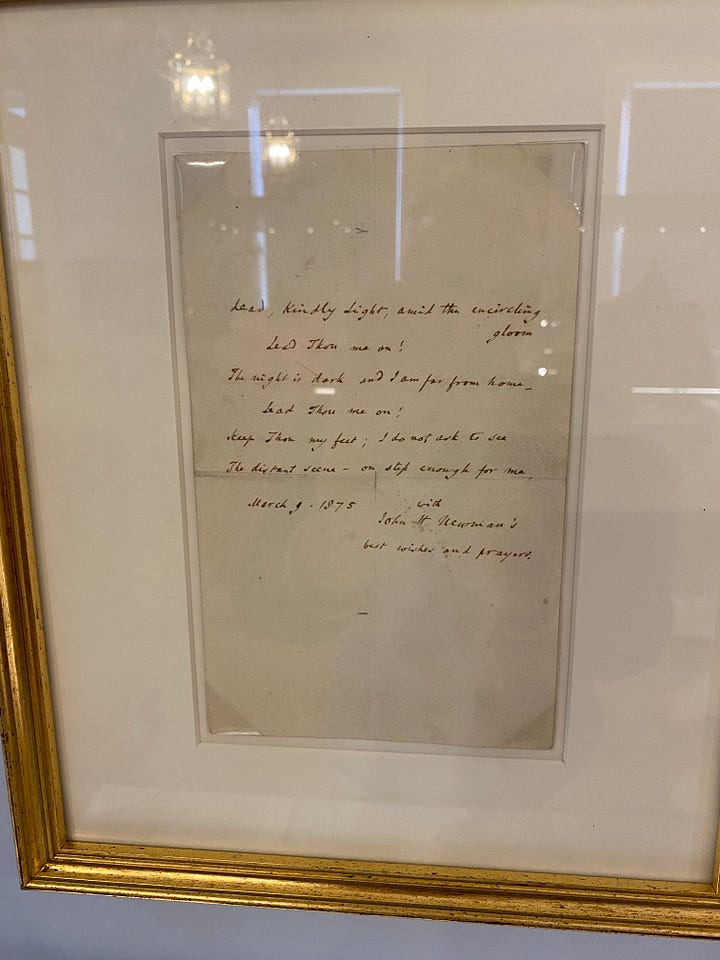

After his conversion to Catholicism in 1845, St. John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890) joined the Congregation of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri, and was soon after authorized by the pope to bring the Oratorian community to England. A house was eventually established in the Edgbaston neighborhood of Birmingham, which is where Newman lived for the second half of his life. On the ground floor of the house next to the Oratory church is the Newman museum, open to the public by appointment only.

(A portrait of St. John Henry Cardinal Newman)

Our flight landed in Birmingham around noon, so we had plenty of time to change our money and catch our breath in an airport café before getting into a taxi for Edgbaston. We then had a late and leisurely lunch at the Del Villaggio Restaurant on Broad Street, which was close enough to the Oratory, about half a mile, for us to walk there—wheeling our massive suitcases. Believe me, after the delicious pasta at Del Villaggio, we needed the walk.

My wife Amy and I are deeply in debt to Mr. Daniel Joyce, curator of the Newman museum, for being such a genial host, for answering our questions, and for calling us a cab after the 5:45 p.m. Mass so that we could get to the train station (we went on that evening to Stratford-upon-Avon).

(Yours Truly outside the Oratory House. The gallery below features the Newman museum. Newman was created a cardinal in 1879 by Pope Leo XIII, and his cardinal’s vestments and zucchetto (skullcap) are on display.)

The Domed City

In the lectures that became The Idea of a University, Newman argues for a truly “liberal” education, an education that liberates and frees. Liberates us from what?

From what we might call the “domed city.”

The domed city is one of the enduring tropes of science fiction. Its first instance goes back to 1881 and William Hay’s novel, Three Hundred Years Hence, and we find it still in play in Stephen King’s 2009 bestselling thriller, Under the Dome, which since has been developed into a streaming series. The domed city trope is used in different ways by different writers, but in many of these science fiction stories the dome technology is used to protect what’s left of the human community from environmental disaster. In Julianna Baggott’s popular Pure trilogy, for example, the first volume of which was published in 2012, the human beings who survive a nuclear war take to a domed city in order to protect themselves from radiation.

At the dawn of the modern age, in the 17th century, there was great optimism regarding the promise of the new experimental sciences. Francis Bacon (1561-1626) and René Descartes (1596-1650), two of the founding fathers of the age, understood the point of these sciences to be, in Descartes’ words, “the mastery and possession of nature.” The novelty of this ambition should not be missed. Ever since God commanded Adam to cultivate and care for the garden he had created for him (Genesis 2:15), human beings have used their art and ingenuity to make use of nature in order to benefit themselves. But for the pre-modern mind, this use of nature was meant to be a co-operation with nature’s, and indeed with God’s, purposes. It was understood as a call to stewardship. For the modern mind, by contrast, the mastery and possession of nature is understood as complete subjugation. Nature has no purposes of its own to be respected and cooperated with; it is mere “stuff” to be manipulated according to the will of those with the power to do so. With modernity, therefore, comes both a novel understanding of nature and a novel understanding of the relationship of human beings to nature.

But while this aspiration to dominate nature has yielded innumerable technological triumphs, it has also revealed itself as a kind of virus that seeks, in C.S. Lewis’s words, to abolish human beings themselves. This is because the domination of nature includes human nature, and when human beings are perceived as mere “stuff,” then there is no end to the mischief that might be worked on humanity in the name of progress.

Which brings us back to the domed cities of science fiction. What is the point of so many uses of this trope if not an attempt to find an image for the way in which humanity is forced to hunker down in fear when the work of our own hands, the virus we have created, gets out of control? In such fictions the dome is a refuge, but also a place of deep discontent. For although safety is secured under the dome, it is also clear that the dome cuts off its denizens from many of the most human things. The dome keeps the remnant of humanity protected, yet isolated and fearful.

Interestingly, during the worldwide COVID-19 lockdown in spring 2020, Will Gompertz, arts editor for the BBC, compared the lockdown to the dystopia described in E.M. Forster’s 1909 short story, “The Machine Stops,” a story which features, in a variation of the domed-city trope, human beings living in underground rooms, where all needs are met by the “Machine.”

The Dome of the Workaday World

Even more interestingly, the German Thomist philosopher Josef Pieper, in a powerful essay entitled “The Philosophical Act,” first published in 1952, makes explicit use of the dome image to capture the predicament of modern man. For Pieper, the dome represents “the bourgeois workaday world” of providing for our daily necessities. The workaday world is the sphere of man understood as a mere organism-in-an-environment, a being meant only to satisfy its needs for food, shelter, clothing, health care, shallow entertainment. It is a world in which the demands of work, understood in purely utilitarian fashion, have pushed out all other aspects of the good life for human beings.

In “The Philosophical Act” Pieper does not say much explicitly about the role of science and technology in creating the dome that is this world of “total work.” Still less does he talk about the fear of the work of our hands—the fear that is a key theme of John Paul II’s first encyclical, Redemptor Hominis (see paragraph 16). Pieper focuses, instead, on the fatigue and dullness that result from being hunkered down in the workaday world—a fatigue and dullness that would seem to mask the fear of what human beings have created. Life inside the dome of the workaday world is characterized by “a feeling of strain, of being overwrought and overdone—and this fatigue is only relieved in appearance by the breathless amusements or the brief pauses that punctuate its course: newspapers, a cinema, a cigarette.”

Piercing the Dome of the Workaday World

It is not that work is a bad thing. Work is a genuine good. But the satisfaction of what Pieper calls “the common need,” which is satisfied by work, does not address other and more important aspects of “the common good” of human beings. In order to realize this higher dimension of our being, we must, in Pieper’s phrase, “pierce the dome” of the workaday world.

What does Pieper mean by this metaphor of “piercing the dome”? He means, with Cardinal Newman, the pursuit of those free activities that transcend the world of work: the activities of mind and will engaged in that which is “for itself,” and not merely for the sake of achieving some practical result in the world, however beneficial. “A properly philosophical question always pierces the dome of that encloses the bourgeois workaday world….” The wonder that motivates philosophy is incommensurable with the striving we undertake to satisfy our daily needs. And it answers to something higher in us, a capability that Aristotle does not hesitate to call “divine.”

Other Shocks to Our Complacency

But there are acts other than philosophy that pierce the dome: “Man also steps beyond the chain of ends and means, that binds the world of work, in love, or when he takes a step toward the frontier of existence, deeply moved by some existential experience, for this, too, sends a shock through the world of relationships, whatever the occasion may be—perhaps the close proximity of death.”

Pieper also mentions poetry, and indeed “any aesthetic encounter,” as capable of sending a “shock” to our complacent system, enabling the self to transcend the debased condition of living like an organism-in-an-environment and achieving the truly liberating condition of a human being fully alive to the truth, goodness, and beauty of reality.

(Above is the standing desk at which Newman wrote his great spiritual autobiography, Apologia Pro Vita Sua.)

Newman on Truly Liberal Education

In The Idea of a University Newman distinguishes two kinds of education:

“the end of the one is to be philosophical, of the other to be mechanical; the one rises toward general ideas, the other is exhausted upon what is particular and external.”

Newman takes pains not to denigrate a mechanical or practical education for what it is. But a mechanical education is an education to get along well in the workaday world. Everyone needs such an education to one extent or another, but if education is reduced to the mechanical, then something substantial and marvelous is lost. We are not taught how to pierce the dome of the workaday world, to move beyond the satisfaction of daily needs to the fulfillment of our spiritual beings in the realities that transcend the senses.

Newman writes, speaking of the knowledge that is gained by a philosophical education:

“When I speak of Knowledge, I mean something intellectual, something that grasps what it perceives through the senses; something which takes a view of things; which sees more than the senses convey; which reasons upon what it sees, and while it sees; which invests it with an idea.”

A knowledge that sees more than the senses convey. In my next post, I want to reflect further on what it means to see in the way Newman describes.

“Newman’s Own” Rosary.

And Chalice!

A photograph of Cardinal Newman.